David calls out in Psalm 103, ‘Bless the Lord, O my soul, and all that is within me, bless his holy name!’ (Psalm 103:1)

Believers have always had a special reverence for the name of God, both for his ‘name’ in the sense of reputation, but also for the name by which he revealed himself. In Jewish tradition, the name of God, which in Hebrew is יהוה (YHWH), is never pronounced. This is also why the term ‘Tetragrammaton’ (meaning ‘four letters’) is used to refer to the name יהוה. With some exceptions1, this has been carried over into modern translations by rendering YHWH as Lord in small capitals.

In English translations, the small capitals distinguish ‘Lord’ from the title ‘lord’ or ‘master’—אָדוֹן (adon or adonai). Sometimes we find both the title ‘Lord’ and the Tetragrammaton used together. In Genesis 15:2, for example, we find Abram asking, ‘O Lord God (אֲֲדֹנָי יֱהוִה, adonai YHWH), what will you give me?’ The problem with using ‘Lord’ as a (correct) translation of adonai and also to represent the Tetragrammaton becomes immediately clear. For the sake of consistency, Genesis 15:2 should be ‘Lord Lord’, but here and elsewhere our translations use the more elegant, ‘Lord God’, now rendering YHWH as ‘God’ in small capital letters.

Historically, the name of God has been treated with respect. The story of how this respect played out in the early Greek manuscripts of the Bible tells us a similar, but complicated story. Perhaps surprisingly, the results of this story are to be seen in many of our churches even today.

The Greek translation of the Old Testament

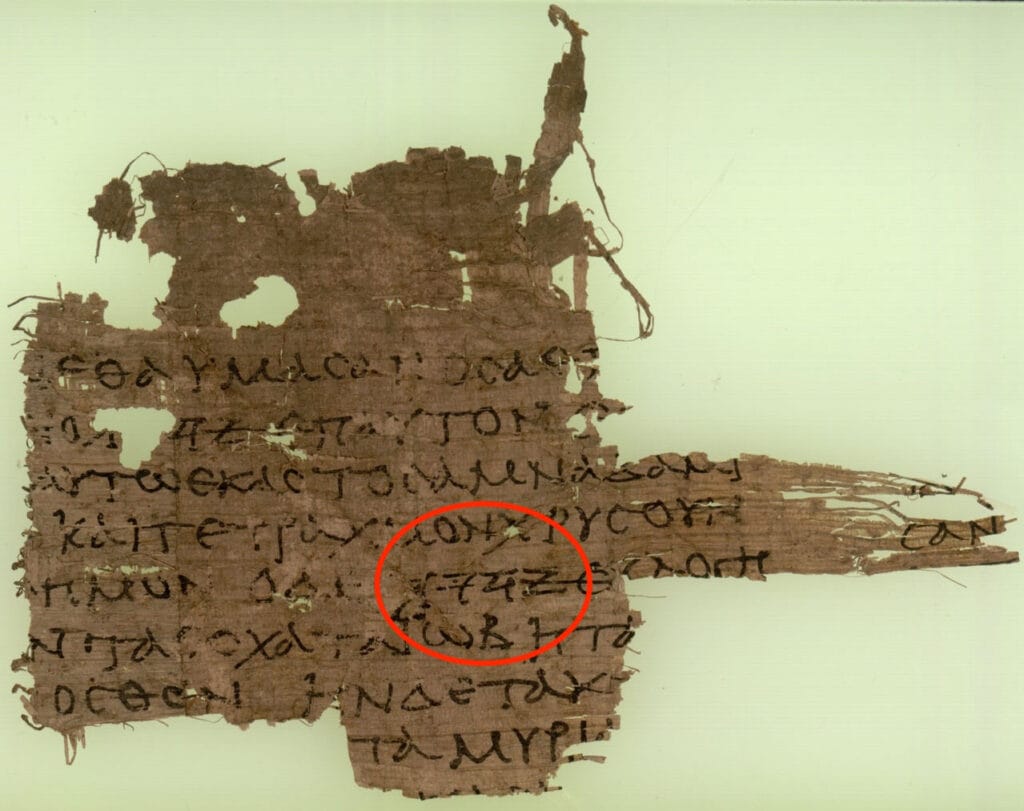

The Hebrew Bible, which Christians know as the Old Testament, was translated into Greek in the centuries before the birth of Christ. We only have sporadic manuscript evidence from this time, but it seems that there is a pattern to be found: whenever the Tetragrammaton is found in the Hebrew text, the oldest Greek manuscripts do something special. Instead of attempting a translation or using some sort of Greek version of the Hebrew letters, these manuscripts have the divine name written in Hebrew characters. A reader of such a manuscript would read the normal Greek translation and then suddenly come across a break in the Greek text, encounter four Hebrew letters, and then resume the normal Greek text.

Often we find the Tetragrammaton written in the familiar square script יהוה, but occasionally we also find the name written in the old Hebrew script.

This may go back to a similar phenomenon found in, for example, a Qumran Psalms scroll written in the Hebrew square script, which uses the palaeo-Hebrew script for the Tetragrammaton (11QPsalms).

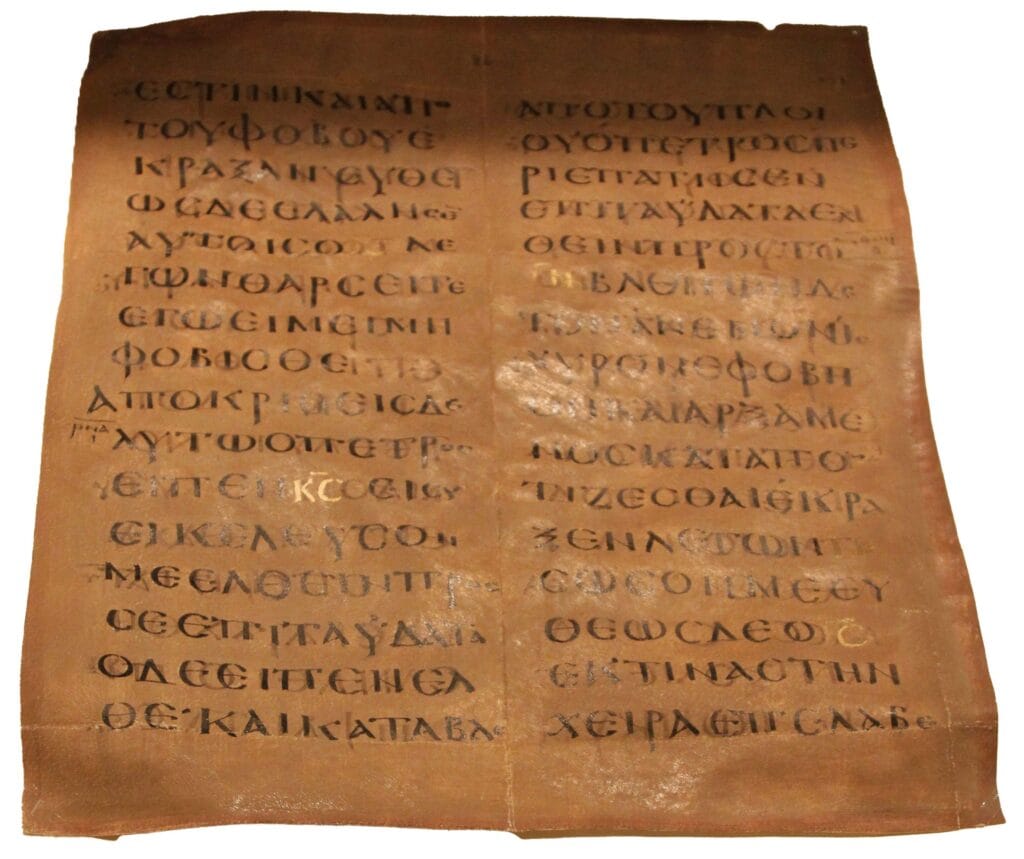

When readers encountered the Tetragrammaton in Hebrew, they pronounced it adonai, meaning ‘Lord’. It is likely that the same happened in reading out the Greek translation, but instead of using the Hebrew adonai, they used the Greek word for ‘lord’: κύριος (kurios). This explains what happens when the Greek New Testament cites the Old Testament. In places where the Greek manuscripts of Old Testament texts might well have had Hebrew letters for the Tetragrammaton, we find these texts cited in the New Testament with κύριος (kurios, lord).

In the early centuries of the Christian era, we find this practice continuing in two forms. Sometime between around AD 230 and 240, the Christian scholar Origen produced a monumental work on the Greek text of the Old Testament, normally called the Hexapla. The goal of this work was to compare the various Greek translations with the Hebrew text. The first column contained the Hebrew, the second a transliteration into Greek letters, and the remaining columns the translations of Aquila, Symmachus, the Seventy, and Theodotion. Some parts of the Hexapla have been preserved and they show that Origen used the Tetragrammaton in Hebrew in each of the four Greek translations.

There is another echo of Greek manuscripts containing the Hebrew Tetragrammaton in a letter Jerome sent to Marcella (Jerome, Ep. 25). In this short letter, Jerome explains ten names of God, and says about the Tetragrammaton that it is not to be spoken (using both the Greek ἀνεκφώνητον and the Latin ineffabile). Then he adds that some who do not understand this, used to read ‘PIPI’ (ΠΙΠΙ in Greek letters) when they encountered the Hebrew letters in the Greek books, because the Hebrew letters יהוה have a superficial likeness to ΠΙΠΙ. Jerome does not seem to suggest that the Tetragrammaton was copied as ΠΙΠΙ, but, because of the similarity of the letters, it was read as ‘PIPI’ by those who did not understand what was going on. In the Cairo Genizah fragment of the Hexapla in Cambridge, it seems indeed that instead of the Hebrew we have the Greek letters ΠΙΠΙ.

Christian innovation

When the early Christians started writing and copying the words of Scripture, they were faced with a difficult dilemma. Many would have had a background in Judaism and been aware of the scribal practices surrounding the Tetragrammaton. But now that they had learned about Jesus the Messiah, who is God, the question arose about how to show respect for the divine name in writing.

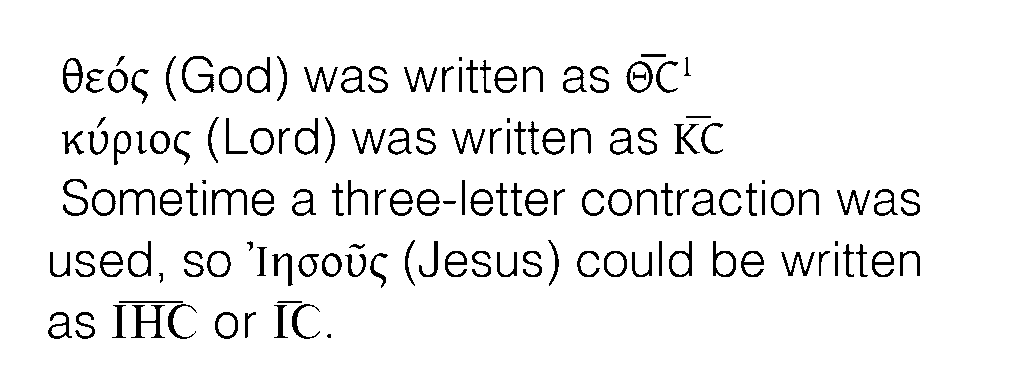

As mentioned already, the first step was to use the Greek word κύριος (‘Lord’) for the Tetragrammaton in quotations from the Old Testament. The second step, which must have happened early on, was to treat not only the word κύριος (Lord), but also the words θεός (God), Ἰησοῦς (Jesus), and Χριστός (Christ) in a special way, setting them apart from the rest of the text. The divine name had turned into a group of words that were treated with special respect.

This respect was shown by contracting the noun and writing only the first and last letters, see image below for how this looked.

These so-called nomina sacra (‘sacred names’) are already present in our earliest manuscripts.

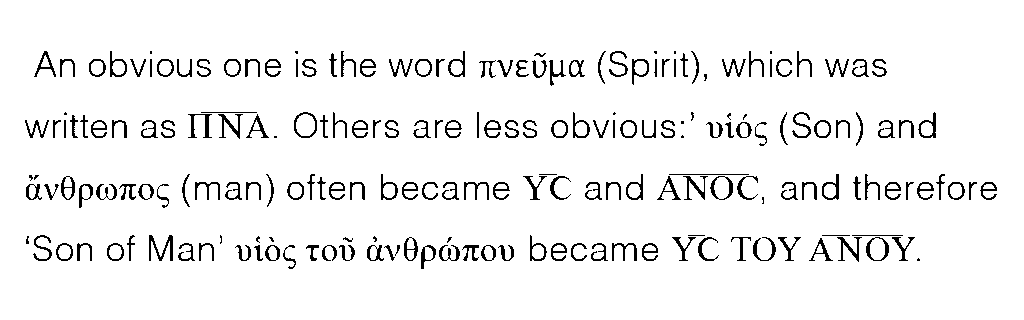

Very early on, the use of these contractions for ‘sacred names’ spread to other words as well:

Other terms that were treated this way at times are father, mother, Israel, Jerusalem, heaven, saviour, cross, and David. Clearly there was an expansion of this practice that went way beyond its initial extent. The inclusion of ‘mother’, for example, demonstrates the growing veneration for the mother of Jesus in the early centuries.

A problem arises with the word ‘lord’, as it is used both to refer to God and Jesus Christ, and also for ordinary human beings, as in English with a lord and his servants. Likewise, the word ‘spirit’ (πνεῦμα) is also used for ‘wind’ or even ‘evil spirits’. Even the name Jesus is not simple as there are other people in the New Testament with that name besides Jesus Christ. (Perhaps most notably, the exact same name is used in Greek to refer to the Old Testament Joshua). How did scribes cope with this diversity? The situation in the manuscripts is far from uniform. Some scribes distinguished carefully between sacral and non-sacral use. For many others, the practice became simply a feature of manuscript copying and they made little distinction between the ways that such words were used.

One of the early languages that took over the use of nomina sacra was Latin, though here the practice is restricted mostly to the four words of the core group and ‘Spirit’. Interestingly, in the case of the name Jesus, Latin did not simply apply the contraction to the Latin IESUS but retained the three-letter Greek contraction, now written in Latin characters:

I̅H̅S̅

These three letters, with the overbar, can still be seen in modern churches (see header image), though in popular opinion the long history of this abbreviation is often forgotten. It stands for Jesus, and is a nomen sacrum, a reverential scribal treatment, of the name that was seen to be worthy of receiving a similar special treatment as the Tetragrammaton received in the earliest manuscripts of the Greek Old Testament.

October 17, 2024

Notes

Images in order of appearance:

Header: IHS in Christ Church, Cambridge.

The Tetragrammaton in Paleo-Hebrew © Digital Corpus of Literary Papyri. Courtesy of The Egypt Exploration Society and the Faculty of Classics, University of Oxford.

Nomen sacrum for κύριος written in gold, © Tilemahos Efthimiadis, used under a Creative Commons licence (CC BY-SA 2.0).