Just before Jesus is handed over to be crucified, Pontius Pilate presents the crowds with the choice to release one of two prisoners. The first is described as ‘a notorious prisoner’ (Matthew 27:16), ‘someone who had committed murder in the insurrection’ (Mark 15:7), while Pilate knows full well that the second, Jesus, had been handed over in envy.

Two options for the first prisoner’s name are visible in popular modern translations of Matthew 27:16–17:

And they had then a notorious prisoner called Barabbas. So when they had gathered, Pilate said to them, “Whom do you want me to release for you: Barabbas, or Jesus who is called Christ?”

ESV

At that time they had a well-known prisoner whose name was Jesus Barabbas. So when the crowd had gathered, Pilate asked them, “Which one do you want me to release to you: Jesus Barabbas, or Jesus who is called the Messiah?”

NIV

A few Greek manuscripts do have this expanded name for Barabbas in Matthew 27:16–17, namely ‘Jesus Barabbas’ instead of simply ‘Barabbas’. Of course, this longer name heightens the dramatic contrast, ‘Who do you want me to release to you, Jesus Barabbas or Jesus who is called Christ?’ The crowd has a choice between two Jesuses, one arrested for murder, and the other, the son of God.

Despite the obvious preachability of this textual variant, it is unlikely to be what Matthew originally wrote. The variant has limited support in the surviving manuscripts of the New Testament; none of the manuscripts that have the name ‘Jesus Barabbas’ come from before the tenth century. However, a closer look at the full evidence shows that the variant has an impressive pedigree and goes back a long way in church history.

Back to the manuscripts

The most direct evidence for the variant comes from a manuscript written not in Greek, but in Syriac, located in St Catherine’s monastery on Mt Sinai, and was first identified by the Scottish biblical scholars, Agnes Smith Lewis and Margaret Dunlop Gibson, in the late nineteenth century. This manuscript is a palimpsest, meaning that the parchment of the original text (the four Gospels in Syriac) was later re-used and overwritten with a different text. The older, underlying text of the manuscript which testifies to the name ‘Jesus Barabbas’ may come from as early as the fifth century—five centuries before the earliest attestation in a Greek Gospel manuscript. So in this Syriac translation we have evidence that the alternative reading was perhaps more widely known than our tenth century Gospel manuscripts would suggest. To date there is no other direct manuscript evidence in any other language of Barabbas being called ‘Jesus Barabbas’, yet there is more evidence to take into consideration.

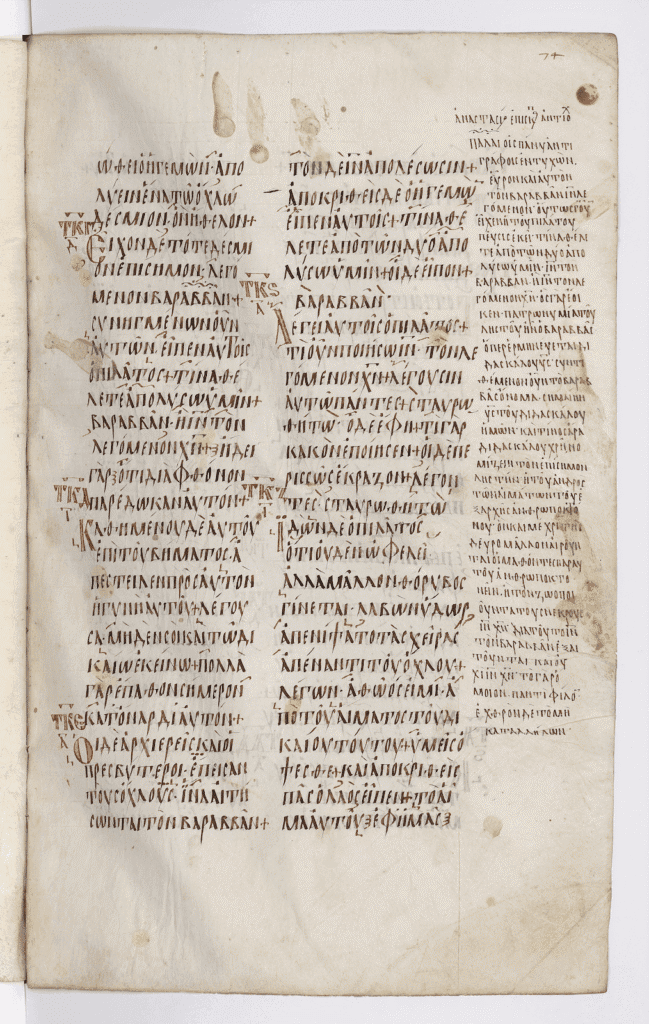

There is a Gospel manuscript written in majuscule letters (in contrast to the more common minuscule script we find in most New Testament manuscripts) from the tenth century that contains about a dozen or so marginal comments spread out across the four Gospels (majuscule S028; Vat.gr.354). These comments betray a historical interest in certain people that are mentioned. So for example, next to the genealogy of Jesus in Matthew it explains how Jesus’ ancestor Matthan is the link between Mary and Elisabeth (Matthew 1:15). At Matthew 27 it has a note that starts like this:

“But in very old copies I encountered, I found also Barabbas called Jesus. So therefore the question of Pilate is there, ‘whom do you wish from the two that I release to you? Jesus Barabbas or Jesus who is called Christ?’ For it seems that the patronym of the robber was Barabbas, which is interpreted as ‘son of the teacher.’”

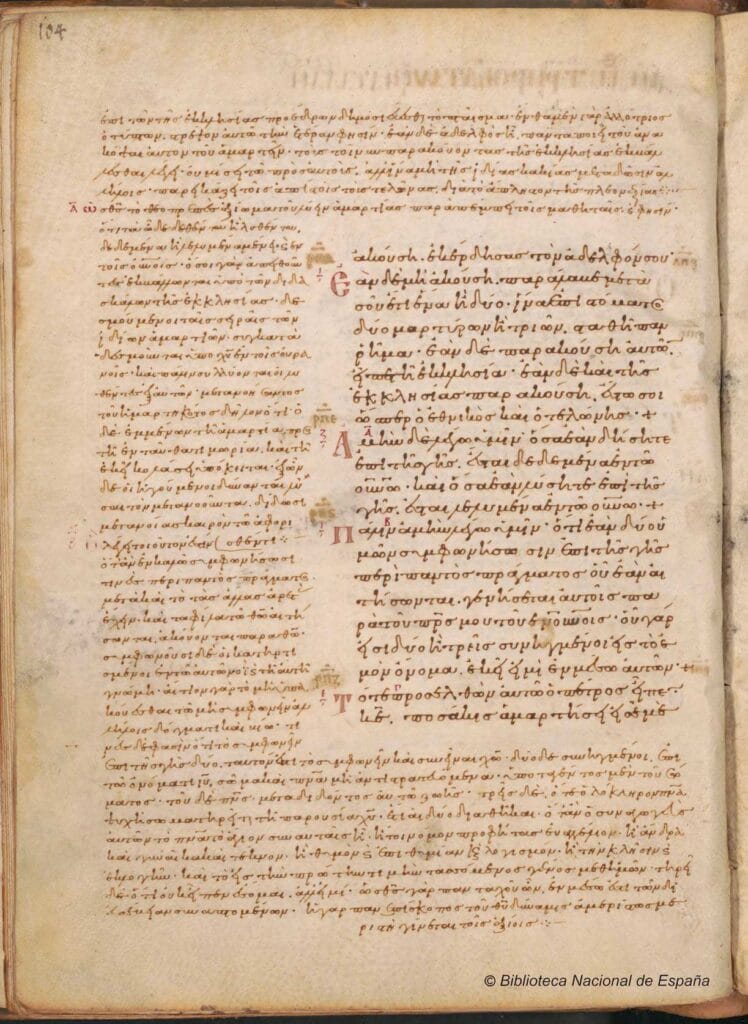

Where does this note come from? Both the majuscule manuscript discussed above (S028) and a contemporary minuscule manuscript (minuscule 200; Florence, Bibl. Laur., Conventi Suppressi 159), which has this same note, attribute it to the bishop Anastasius of Antioch. Yet there is a likelier candidate: the note is found in exactly this form within a larger commentary on Matthew by a certain Petrus of Laodicea, who probably lived in the sixth century (and confusingly, sometimes his commentary appears under the name of John Chrysostom). Petrus of Laodicea’s commentary on Matthew is quite popular and is found often in the margins of mediaeval manuscripts of the Gospels (see the image below for an example). It is also clear, however, that though Petrus of Laodicea is responsible for the wording of the note, he is most likely summarising someone else, as he does throughout his commentary. But whom?

Here it is the Latin translation/reworking of the Matthew commentary by the third-century theologian and scholar, Origen, which helps us out (normally called the Commentariorum Series). The same thought, in a much fuller form, is discussed in the commentary, but with a slight twist. Instead of assuming a text that has Jesus Barabbas as the variant, it comments from the perspective that ‘Jesus Barabbas’ is the main text, and just ‘Barabbas’ is the variant. Whichever way it appeared in Origen’s original commentary in Greek, it is clear that the variant ‘Jesus Barabbas’ goes all the way back into the third century, and that much later manuscripts did preserve an old, though incorrect, reading.

So where did it come from?

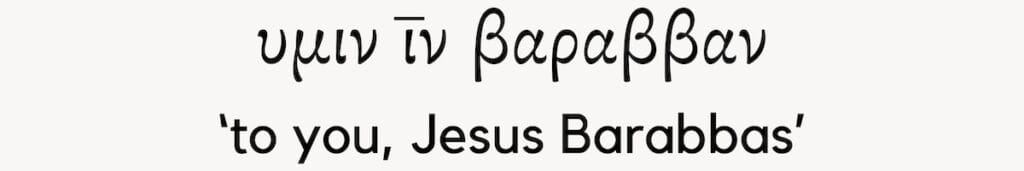

Finally, how did such a strange error come into being? In the nineteenth century, the biblical scholar, Samuel Prideaux Tregelles, offered the most probable explanation. He noticed that in Matthew 27:17, in the clause, ‘Who do you want me to release to you, Barabbas or Jesus’ the last two letters of ‘to you’ form the standard abbreviation used for ‘Jesus’. The name ‘Jesus’ was one of the words consistently abbreviated by writing only the first and last letter(s), one of the so-called nomina sacra. A scribe, in anticipation of the name Jesus, could easily have been tricked into reading the final letters of υμιν (‘to you’) twice, leading to a text that reads:

If this explanation is correct, it would mean that all the confusion that left its traces for at least 700 years and longer in the manuscript tradition goes back to a simple, common copying error.

So what do we do when modern Bible translations reproduce copying errors?

Firstly, we can be encouraged that Bible translation is a work in progress. Translations like the NIV and ESV need periodic updates because our knowledge becomes more precise. They are the careful work of teams of scholars who scrutinize many suggested changes to the text.

Secondly, we can be encouraged that this process is not concealed from view. It is no secret that the ESV and NIV render these verses differently, or which manuscripts each reading relies on. The problem is mentioned in the footnotes. We are fortunate enough to have a variety of modern translations at our fingertips and can easily compare the different conclusions formed by the translation committees.

Thirdly, we can be encouraged and compelled by the reminder of how the Bible’s text has been transmitted through the centuries. Thanks to the surviving manuscript evidence we can be confident in the text of the New Testament. We can make detailed investigations into individual words in these manuscripts, and in the majority of cases, we can recover the exact words New Testament authors wrote.

See also our notes on this in the THGNT.

April 14, 2022