Following the Bible's paper trail

Article

13th December 2019

Before New Testament translators can begin their task, they need good base texts in the original language that are as close as possible to the wording received by the earliest readers. Unsurprisingly, given the age of these writings, we don’t have one single authoritative version, but rather thousands of early “witnesses” ranging from complete copies to manuscript fragments with just a few words or even letters.

Bible scholars examine these pieces of evidence, assessing the small variations that inevitably creep in between documents, and deciding what the most accurate form of words is likely to be. Dr Dirk Jongkind is the editor of Tyndale House’s version of the New Testament in its original Greek. Here he explains what early manuscripts are available, and how scholars use them to present the text as accurately as they can.

The numbers

Humans like to count things. We like to know how many steps we’ve taken, how many birthday cards we received, how many days until Christmas. So it’s not surprising that scholars are keen to know how many manuscripts we have for the New Testment. It’s encouraging to discover that even the most cautious academics affirm that there are more than 5,000 known hand-written documents of the New Testament in its original language. Before we get too carried away with our counting, however, it’s worth pausing to ask what this number actually tells us.

The period during which the New Testament text was copied by hand lasted until the end of the 15th century, and, as one would expect, many more recent manuscripts were preserved than older ones. Though parchment can survive a long time in ideal circumstances, many ancient documents have simply decayed and perished. This is even more the case for papyrus, the other material used as “paper” — only in rare circumstances will it have survived into modern times. Consequently, the calculation of over 5,000 manuscripts before the first printed Greek New Testament is heavily tilted towards the most recent times.

Still, a good number of early manuscripts exist. The dating of manuscripts is an area of much debate, but according to my count we have just over 400 listed items from the 9th century and before. Remarkably, this early group of manuscripts is quite evenly distributed over the centuries — apart from the second century where we have only a few (and no, as yet we do not have anything that is generally regarded to be from the first century).

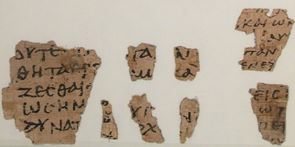

The fragments

Obviously this number of roughly 400 is much lower than the 5,000 or more with which we started. But even this number requires further thought. Everyone who has worked with manuscripts knows that there is an enormous disparity in the amount of text that a single manuscript can represent: both a surviving single leaf and a complete New Testament count as a single manuscript. In fact, complete leaves are pretty exciting for scholars given that many of the early manuscripts give us much less text. If we take only the manuscripts that contain “text” from at least 25 verses, the numbers change dramatically (note, a single letter from a verse is sufficient to be counted). For comparison, 25 verses is the length of Jude and Philemon.

It appears that the vast majority of early manuscripts are fragments, and often very small fragments at that. Papyrus is heavily overrepresented amongst these fragments up to the 6th century. Since papyrus mainly survived in the dry climate of Egypt, they come from a geographically limited area. Which leads to the question, what is the value of these early but small pieces with very limited text?

First, a little bit of testimony to some of the text is more informative than nothing at all. It enables us to make tiny spot checks of individual words or phrases. We learn about early copying errors that were made and about spelling patterns. Some variants in the wording known only from much younger manuscripts turn out to be quite a bit older, and some variants may have been local or individual errors, but are nowhere to be found later in the transmission of the text.

We also learn that the New Testament was copied frequently. The manuscript evidence tells us that there was a distinctive Christian book culture. From very early on, Christians preferred the codex form (like a modern-day book) over the scroll, which was used for “real” literature well into the 4th century. From as far back as the evidence allows us to see, Christians were using a set of in-house abbreviations for a group of special words (nomina sacra, or “sacred names”). Words such as “God”, “Jesus”, “Christ”, and “Lord”, were written by using only the first and last letter with an overhead stroke. There is no real parallel for this phenomenon. So, even though the early small papyrus fragments give us sometimes little more than a couple of dozen letters and come from a restricted area, they are still useful and can even help us to assess the balance of manuscript evidence with greater precision.

At the same time the fragments leave us with many unanswerable questions. Why do we have so many manuscripts that consist of a fragment from only a single page? What does this tell us about the chances of manuscripts’ survival in general if so many of the other pages are completely lost? And was the situation in rural Egypt any different from that of the churches in the big cities? In the late 2nd century the church father Irenaeus wrote about copies of the text of Revelation that had the number of the beast as 616 instead of 666. He had many reasons to reject the lower number, but one of them was that the “oldest and approved” copies of the text all read 666. It stands to reason these approved copies did not end up on the rubbish heaps of Egypt like many of our papyrus fragments, but were the treasured possession of some central church. So do we have any manuscript remains that could come from a more central part of the transmission of the New Testament?

Large manuscripts

At the other end of the scale from small fragments, we find two manuscripts from the early period that contain (nearly) all the New Testament (Codex Sinaiticus and Codex Alexandrinus, from the 4th and 5th century), in addition to two manuscripts that contain much of it (Codex Vaticanus and Codex Ephraemi Rescriptus, also from the 4th and 5th century).

It may strike us as strange that there are so few complete New Testaments. However, the majority of surviving manuscripts that are more or less complete were written to contain only part of the NT. We have manuscripts containing the four gospels, or manuscripts of Acts and the General Epistles (James to Jude), or of the letters of Paul, or containing some cross-over between these. Complete Greek New Testaments are rare, and as far as we can see from the evidence, most churches would have had the New Testament only as a library of books rather than in a single volume. These large Bibles, in addition to the nearly complete manuscripts of sections of the New Testament, are highly valuable as tools to study the history of the text. Not only are they large enough to enable assessment of their copying quality and an analysis of their strengths and weaknesses, but they also have evidence of how the text was used in the form of notes in the margins, liturgical annotations, and sometimes a complex layering of corrections on the text.

The complete manuscripts — when were they produced?

Codex Sinaiticus can be dated confidently to the 4th century.

There have been at least three different scribes identified who wrote different portions of the manuscripts all in the same bookhand (“font”). A 4th century date also works well for some of the corrections made in a different script. Moreover, Sinaiticus includes a reference system designed to aid comparison of the various gospels, called the Eusebian apparatus, which was designed in the early 4th century.

Codex Vaticanus looks very much like Sinaiticus.

The letters are more or less similar, as are the way in which corrections are formatted, the endpieces to the books, and the whole layout. It is clear, however, that one is not a copy from the other, there are too many differences in their actual text. Even though Vaticanus lacks the Eusebian apparatus, these two manuscripts share so many similarities in their design that most likely they come from a similar time in history.

Dating

While we can be fairly sure that, for example, Codex Sinaiticus comes from the 4th century, there is far less certainty about manuscripts believed to be from the first four centuries. Dating of most manuscripts is done by comparing their handwriting with other examples. Some of these examples may have a date written on them, or are written on the back of a dated and re-used document. Often, however, we have to rely on a reconstruction of how a certain script developed over a number of centuries — assuming there is not too much overlap between the various phases of a specific script — and then assign the manuscript to the most probable time frame within that development. The basic assumption of this method is intuitive: my parents’ handwriting is different from my generation’s, just as my children have learned to write in a different way. So far so good. Yet there was a time that these three generations overlapped and all three “phases” were being written at the same time. Something comparable is found when we look at books printed in the 19th century. There is something about the layout and the font that gives it away as being from the past. Still, a modern publisher might decide to produce a book that incorporates archaic elements.

All this should encourage us to regard the dates assigned to manuscripts within the limitations inherent in the discipline of palaeography (the study of historical handwriting). And of course, even dating to a particular century puts a manuscript into a fairly artificial box — are we really able to distinguish between a late 2nd and an early 3rd century document?

Weighing the evidence

All these considerations are helpful before we start comparing the actual text of the manuscripts. A tiny fragment with a strange reading will, even though early, carry a different weight from the wording found in a large manuscript that we know has been copied by an able scribe. The dates of manuscripts are important, but they are only a part of what we need to know before we can assess the full value of a textual witness.

It took Tyndale House 10 years to complete its version of the Greek New Testament, examining the manuscripts in minute detail to present the earliest recoverable wording. But to Christians the Bible is unfathomably precious, and worth the extraordinary effort that was expended on every jot and tittle.