Who were the Galatians?

Article

12th June 2025

Ben Gardner considers two possible explanations for who Paul was addressing in his letter to the Galatians.

Christians believe that God receives every human being into his family on the basis of faith in Jesus Christ alone. Note the emphasis on ‘every’. This word underscores the belief that this status is not confined to a specific ethnic group or class, nor is it dependant on a person’s worth by comparison to others. It is for everyone who trusts in Jesus. This profound confession has without doubt shaped the entire course of human history. It is why billions of people across the globe claim membership in Christ’s family today.

I find it fascinating that the most direct treatment of the ‘every’ aspect of this confession in the Scriptures should be occasioned by an obscure people called the ‘Galatians’. It was their crisis in faith, their desertion of the gospel, their mistrust of Paul’s authority, their desire to be circumcised and submit to Torah that compelled Paul to write a letter that has helped shape the way Christians think about freedom, justice, equality, authority, and other issues for two millennia. You cannot consider these subjects in the letter without reflecting on the relational dynamics between Paul and the Galatians. That’s what gives the letter its punch and realism. Humanly speaking, without the Galatians we would lack one of the most faith-giving letters in the New Testament. For all of these reasons, it is worth asking: who were these Galatians?

Regrettably, this question is famously difficult to answer. Many a scholar has had to throw their hands up with Paul and simply admit to the Galatians: ‘I am perplexed about you’ (4:20). Why is it so perplexing? Well, the problem is that Paul could be writing to either (1) ‘ethnic Galatians’ or (2) ‘provincial Galatians’. As you will see in what follows, a good case can be made for both options from Paul’s letter and from the book of Acts.

The ‘ethnic Galatian’ hypothesis

For a Welshman like me, it is exciting to think that there is some connection between my people and the Galatians Paul wrote to, however tenuous that may be. Like the Welsh, the Galatians (Greek, Galatai) trace their roots back to the famous people called the Celts (Greek, Keltoi). However, the Welsh belong to the sub-group known as the Insular Celts, including the Irish, Scots, Manx, Cornish and Bretons, whereas the Galatians are among the Continental Celts, including the Gauls, Helvetti, Celtiberians, and others.

The Galatians ended up in Asia Minor in the third century BC off the back of their military exploits. The most famous of these was in Greece (280-79 BC). Despite the Galatians being on the losing side in the war with the Greeks, King Nicomedes I was impressed enough to employ them as mercenaries in his battle against his brother for the control of Bithynia (278 BC). In return for their assistance, the Galatians were given territory around Ancyra (modern-day Ankara, Turkey), where they became a nuisance, picking fights and grabbing land. Whilst the Galatians were known for bravery and brutality in war, this does not mean that they were particularly good at it. Indeed, according to Polybius’s account of their war with the Romans in 225 BC, the Galatians ‘showed no power of planning or carrying out a campaign, and in everything they did were swayed by impulse rather than by sober calculation’ (Histories, 2.35, trans. Evelyn S. Shuckburgh, Macmillan, 1889). Polybius’s description of the Galatians as impulsive is typical of ancient historical literature.

They were defeated by the Romans and remained under Roman rule from the third century BC onwards. Therefore, whilst there was a stereotype of the Galatians as brave, impulsive and superstitious, they also would have been fairly well assimilated into the Graeco-Roman world by the time Paul was writing his letter.

Did Paul write to this people? When you think about the Galatians’ reputation and how Paul presents them in the letter, it seems plausible. Paul normally addresses the recipients of his letters based on where they reside: ‘to those who are in Rome’, ‘to the church of God in Corinth’, and so on. Galatians follows a similar pattern, ‘to the churches in Galatia’. Yet, later in the letter Paul does something unusual for him. He explicitly identifies them as ‘Galatians’, and ‘foolish’ ones at that (3:1). Is he doing this to play on the stereotype of the Galatians? The Galatians were also known to be fickle and superstitious. Archaeological findings show a people who liberally adopted the worship of the gods of their neighbours, observing strict rituals. Does this help explain their speedy desertion of Paul’s gospel (cf. 1:6) for a ritualistic life under Torah that resembled the practices of their pagan past (cf. 4:8-12)?

There are also certain details that may be specifically aimed at this people group. Take, for example, Paul’s illustration of the child who is no different to a slave when he is under his parents’ control (4:1-3). According to a law textbook from AD 161, written by Roman jurist Gaius, this practice applies only to Roman citizens and one other people group: the Galatians (Institutes of Roman Law, 1.55). Perhaps Paul, a Roman citizen, uses this illustration because it would make sense to this ethnic group?

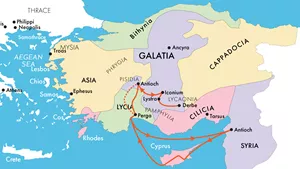

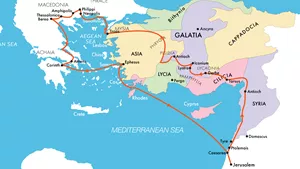

If Paul wrote to the Galatians living in the North around Ancyra, then this could match Luke’s account of Paul’s second mission trip: ‘they went through the region of Phrygia and Galatia, having been forbidden by the Holy Spirit to speak the word in Asia’ (Acts 16:6). Though Luke is silent on the matter, perhaps churches were planted in this visit. Paul later hears of their desire to come under the Torah, and writes this punchy letter to convince them otherwise, giving his version of the Jerusalem council of Acts 15 in his autobiographical narrative from Galatians 2:1-10. However, we should not rule out the possibility that some ‘ethnic Galatians’ lived in the south of the province and could have then been reached by Paul in his first mission trip (Acts 13:13-52).

Many holes can be poked in the above proposal, but it is not a bad case. Up until the 18th century, it was largely taken for granted as the best explanation. However, as historical study advanced in the nineteenth century, it became clear that when Emperor Augustus established the Roman province of Galatia in 25 BC, it extended further south than had previously been realised, including the inhabitants of East Phrygia, Pisidia, and Lycaonia. The church fathers generally missed this fact because Emperor Vespasian began a process in AD 74 that saw the province revert to being just in the north of Asia Minor by the third century AD. This means that the ‘Galatians’ addressed by Paul could be non-ethnic Galatians who happened to live predominantly in the south of the province—Phrygians, Pisidians, Lycaonians, Romans, Greeks, and even Jews. Meet the ‘provincial Galatians’.

The ‘provincial Galatian’ hypothesis

The best argument for the ‘ethnic Galatian’ hypothesis is that Paul explicitly labels his addressees ‘foolish Galatians’. Would he use this label for non-ethnic Galatians?

Some scholars argue that he would. Romans would sometimes refer to people based on their provincial name. Moreover, this letter is unique in that Paul is writing to multiple ‘churches’ in one region. Perhaps the use of ‘Galatia’ and ‘Galatians’ is a convenient way to refer to the churches Paul had established amongst the Phrygians, Pisidians and Lycaonians. Remember, Paul is a Roman citizen, so it is plausible he would adopt Roman labels. Moreover, we know for sure that Paul did plant churches amongst these people on his first mission trip recorded in Acts 13:13-52. In fact, we know that he faced opposition by Jews on this journey, even getting stoned at Lystra before ending up in Derbe. Perhaps this explains the ‘bodily ailment’ that brought him to the Galatians?

After this busy church planting trip, Paul returns to Antioch with Barnabas (Acts 12:20-25). Could this be the moment in Paul’s autobiography when he opposes Peter and Barnabas publicly for removing themselves from table fellowship with the gentiles, implying that gentiles ought to Judaise (Gal 2:11-14)? If so, then you could imagine that this issue of gentile inclusion in God’s people was a live issue, perhaps also affecting the provincial Galatians that Paul had just visited. He then writes a letter to them before attending the Jerusalem council, contending that gentile reception of the Spirit through faith and not works of the law (3:2) proves that God has accepted them and that they should not now submit to the yoke of the law (5:1). Incidentally, the same argument, now articulated by Peter, wins the day at the council (Acts 15). Paul then takes the letter written by the Council to these churches, which Luke refers to by using the provincial label ‘Galatia’ (Acts 16:1-6), adding ‘Phrygia’ because the western part of Phrygia does not fall within the Galatian province.

Many scholars like this proposal because it places Galatians early in Paul’s ministry and explains why he doesn’t mention the Jerusalem council in explicit terms—it hasn’t happened yet. However, other scholars adopt the ‘provincial Galatians’ hypothesis and are happy for the letter to be written later after the council.

Conclusion

Which group is it, then? Maybe you find one take more persuasive than the other. But it is important to know that we have barely touched the surface of the debates in this article. The deeper you go, the more complicated it gets. The ‘provincial Galatian’ hypothesis is favoured by a marginal majority of scholars today, but the ‘ethnic’ hypothesis has not been ruled out. It could even be a mixture of the two. Personally, I slightly prefer the ‘ethnic’ hypothesis because of the details in Paul’s letter, but I admit that geography and a synthesis with Acts favours the ‘provincial’. When interpreting the letter, it is probably unwise to insist on one view over the other.

Some will find this conclusion frustrating. Paul’s letter to the Galatians is so difficult to understand in places, and you can’t help but think that knowing more about who they were would clarify some things. I understand the frustration. But then again, isn’t it fitting that, just as the Galatians had to learn to depend on faith rather than Torah works for justification, we too have to depend on careful exegesis rather than elaborate historical reconstructions for interpretation? Every reader can do that.