The Amorites are mentioned over 80 times in the Old Testament. They crop up between Genesis and the Psalms, mainly in the seven books from Genesis to Judges. Among the people resident in the land of Canaan and mentioned in the Bible, the Amorites stand out because we also find Amorites mentioned in extrabiblical documents from the ancient Near East. The mystery of these people is made more complex as none of the documents that mention the Amorites were written in the Amorite language itself, a language which seems to have disappeared; its only traces remain in proper names and loanwords. So who were these people? Can we know anything about them?

The meaning of ‘Amorite’

Connecting the Amorites known from ancient Near Eastern documents with the Amorites found in the Bible is tricky. When we encounter Amorites in lists of peoples like the one in Exodus 3:8—‘the Canaanites, the Hittites, the Amorites, the Perizzites, the Hivites, and the Jebusites’—we seem to have an ethnic identification. Ethnic categories are formed when people groups identify themselves, or outsiders identify them, on the basis of shared features. These insider and outsider perspectives might in some cases align and reinforce one another, but in others they might diverge and cause the identification to change over time. This means that ethnicities, especially ones that are more than three thousand years old, are notoriously difficult to define.

When we read about Amorites in the Bible, we are getting an outsider’s perspective, rather than the self-understanding of these people. The Bible might mean something different by ‘Amorite’ than other ancient documents which use the same term. In fact, even the same writers may mean different things by ‘Amorite’ in different contexts. In the extrabiblical documents, the term ‘Amorite’ may refer to a direction (‘the west’), to a deity (the god Amurru/Martu), to a language (Amorite), to a region or state on the Mediterranean coast (the land of Amurru), and to people groups with shared identities along less political lines. Unfortunately, all of this makes it difficult for us to interpret these ancient texts. Their writers (and, presumably, their readers) just knew what they meant when they used the term ‘Amorite,’ so they did not take the time to explain it.

Traces of language

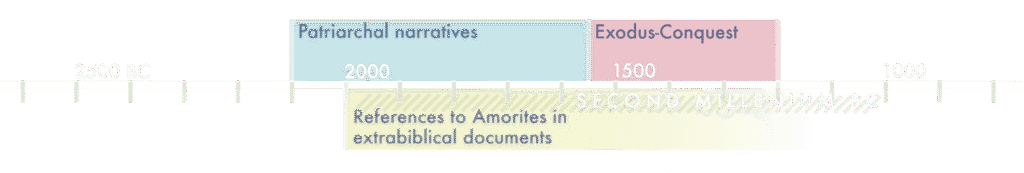

In addition to these ancient uses of the word ‘Amorite’, modern scholars have applied the term to thousands of personal names which occur on cuneiform tablets of the second millennium BC (ca. 2000–1200 BC). These names had meanings, and when their grammar is studied, they prove to be in a West Semitic tongue, related to Hebrew and Aramaic, which may well have been the language called ‘Amorite’ in ancient Near Eastern documents. If so, these names are the only remaining traces of Amorite language, apart from a few Amorite words loaned into other languages. These names appear especially in documents from the early second millennium BC (ca. 2000–1600 BC), when Amorite kings ruled several of the most powerful states of the Fertile Crescent. After this, Amorite names slowly diminished, though some of them persisted into the late second millennium BC and beyond.

In the Bible, Amorites appear in two major units: in the patriarchal narratives (Genesis 12–50) and in the Exodus-Conquest narratives (Exodus–Judges). The break between them corresponds to several generations recounted in only three verses (Exodus 1:6-8), the time between Joseph and Moses. Traditionally, the events recounted in the patriarchal narratives are located in approximately the first half of the second millennium (ca. 2100–1550 BC) and the Exodus-Conquest in the latter half of the second millennium (ca.1550–1200 BC).

Our first encounter with individuals who are called ‘Amorite’ is in Genesis 14:13, which refers to ‘Mamre the Amorite (ha-emori), brother of Eshcol and of Aner.’ These Amorites are distinguished from ‘Abram the Hebrew’ (ha-ibri), with whom they have a pact which involves mutual protection. The name Abram (meaning ‘father is exalted’) is well-attested among the Amorite names; the other names are not, though they are not necessarily out of place in the time and region. Eshcol means ‘grape-cluster’ in West Semitic languages and Mamre may mean something like ‘fatness,’ so two of the brothers’ names may have shared a semantic theme of abundance, a kind of onomastic family resemblance.

While the events of Genesis 14 are told from the point of view of a later time (see 14:1), the traditional dating for the setting of this story is sometime in the first half of the second millennium BC. This, as it happens, was a time when Amorite kings ruled the major political powers of Mesopotamia and the Levant, and some features of the story can be shown to be appropriate for this period. For example, the northern coalition of kings appears to be led by Chedorlaomer (14:4-5), an Elamite king with an Elamite name (meaning ‘the deity Lagamar is a shepherd’). Elam is a country far to the east, beyond Mesopotamia, and the Elamites exerted political dominance as far as the Levant only in the first half of the second millennium BC.

Moreover, in contrast to Abram’s Amorite allies, Abram himself is called a Hebrew (ibri). This word has often been connected with the term abiru (same consonants as ibri, but different vowels), which refers to groups of displaced people. The comparison of these two terms has some problems (and it is best not to get into the details of those here), but in the Amorite age of the first half of the second millennium BC, the parts of some tribes which remained in the steppe with the flocks and herds could be called ibri, like ‘Hebrew’ in Genesis 14:13. Indeed, in Genesis 13 Abram parted from Lot because their respective herds were too big to coexist, and ‘Abram settled in the land of Canaan, while Lot settled among the cities of the valley…’ (13:12). The reference to Abram as ibri, then, may mean that he is someone who resides with the flocks and herds in the country. Such features of Genesis 14 indicate that the events recounted there are best viewed in the framework of the first half of the second millennium BC, and it may be that the term ‘Amorite’ in Genesis 14 carried some of the connotations current at that time. Mamre, Eshcol, and Aner may have been from the land of Amurru along the coast of the Mediterranean or they may have had some sort of Amorite cultural heritage similar to that of the Amorites of the first half of the second millennium BC. But the matter is difficult, and the story is recounted from the point of view of a later time, when ‘Amorite’ may have taken on different connotations.

Exodus-Conquest

In the Exodus-Conquest narratives (Exodus–Judges), the Amorites are typically a people group living in the southern Levant, as in the list in Exodus 3:8. By the second half of the second millennium BC, the political geography of the ancient Near East had shifted and Amorite rulers were no longer in power in most places, though at the city-state of Ugarit kings still traced their lineage back to Amorite ancestors and still had Amorite names. In the coastal region of modern Lebanon, the land of Amurru was still a political entity. References to Amorites in these narratives might refer to people associated with Amurru or to stragglers of the older Amorite age who still viewed themselves as having Amorite identity.

While the Bible certainly represents an outsider’s point of view on the ethnic constitution of Canaan, it clearly has specific notions of what that was. When the spies return from surveying Canaan, they report, ‘The Amalekites dwell in the land of the Negeb. The Hittites, the Jebusites, and the Amorites dwell in the hill country. And the Canaanites dwell by the sea, and along the Jordan’ (Numbers 13:29). The Israelites perceive geographically distinct ethnic identities, with the Amorites of the Cisjordan (the western side of the Jordan River) located in the hill country. Indeed, a number of Amorite leaders are mentioned in the Conquest narrative, including kings of Jerusalem, Hebron, Jarmuth, Lachish, and Eglon (Joshua 10:5-6). Even after the conquest, some of the Amorites remained in this region: ‘The Amorites persisted in dwelling in Mount Heres, in Aijalon, and in Shaalbim, but the hand of the house of Joseph rested heavily on them, and they became subject to forced labour. And the border of the Amorites ran from the ascent of Akrabbim, from Sela and upwards’ (Judges 1:35-36).

In addition to these Amorites of the Cisjordan, there were Amorites of the Transjordan (the eastern side of the Jordan River), who feature prominently in the book of Numbers, as Israel approaches Canaan from the east. What is striking about these narratives is Israel’s specific awareness of the territorial features and history of Amorite lands, knowledge which was based in part on written sources: ‘From there they (the Israelites) set out and camped on the other side of the Arnon, which is in the wilderness that extends from the border of the Amorites, for the Arnon is the border of Moab, between Moab and the Amorites. Therefore it is said in the Book of the Wars of the LORD, “Waheb in Suphah, and the valleys of the Arnon, and the slope of the valleys, that extends to the seat of Ar, and leans to the border of Moab”’ (Numbers 21:13-15). Here, Sihon, an Amorite king, resists the Israelites, who defeat him and take his land. This territory had, in turn, been taken by these Amorites from the Moabites: ‘And Israel took all these cities, and Israel settled in all the cities of the Amorites, in Heshbon, and in all its villages. For Heshbon was the city of Sihon the king of the Amorites, who had fought against the former king of Moab and taken all his land out of his hand, as far as the Arnon’ (Numbers 21:25-26). This snippet from the history of the region may point to a time when people of the land of Amurru on the Mediterranean coast, or perhaps Amorite people who were cultural descendants of the Amorites of the first half of the second millennium BC, came to the Transjordan and made their home there by force. In any case, these Amorites appear to have been outsiders to the Transjordan as the Israelites were. More importantly, they were the only people in the Transjordan whom the Israelites were allowed to conquer, since the Israelites were distant relations of the Edomites, the Moabites, and Ammonites (Deuteronomy 2:1-25).

What was The Book of the Wars of the LORD

A lost document referred to and quoted in the Old Testament only once (Numbers 21:14). We know almost nothing about it other than what we can infer from the text in Numbers. We know that it was a textual source, which was available to the author of the text in which it is quoted, that it was presumably about Israelite wars, and that it contained geographical information about the Transjordan region.

To return to the ethnic list with which this article began (Exodus 3:8), it seems likely that such lists function as a kind of summary of the peoples of Canaan which Israel was to conquer (Exodus 23:23). While this would include the Amorites of the Transjordan (east of the Jordan), these were conquered before the death of Moses, and the remaining Amorites were in the hill country in the Cisjordan (west of the Jordan) (Joshua 11:3). Indeed, ‘Amorites’ is occasionally used as a catch-all category for the peoples of Canaan in general, as when God observes to Abram that ‘the iniquity of the Amorites is not yet complete’ (Genesis 15:16). This implies that God was monitoring the progressive build-up of iniquity in Canaan, which he would punish through Joshua and the Israelites (also Joshua 24:15,18). The use of the term ‘Amorites’ in the Bible, then, extends beyond the senses of the word in the extrabiblical documents, to a theological sense, as the objects of God’s wrath (and occasionally his grace: Joshua 2:8-21; 6:22-25) and, later, as means of testing the faith of Israel (Judges 3:1-6).

Our sources of knowledge about the past are often hard to interpret and their preservation is fortuitous. The term ‘Amorite’ meant different things at different times to different people, so it is not obvious how references to Amorites in the Bible relate to Amorites in extrabiblical documents. But in the study of ancient history we never know as much as we would like and we should resist the temptation to sensationalise in the absence of evidence. We simply must come to terms with this sort of uncertainty.

December 9, 2022

Notes

Image: Walters Art Museum, Baltimore. WAM 42.669 (CC0 1.0).