One possible answer would focus on language. The Masoretic Text is written in Hebrew; the Septuagint is written in Greek; the Vulgate is written in Latin. But this answer wouldn’t quite explain why these terms (or rather – what these terms refer to), are so crucially significant for us as Scripture-treasurers.

Imagine a high profile court case. This particular case turns on one key conversation, overheard by multiple witnesses. One by one the witnesses approach the stand, and each of them recites verbatim, to the best of their ability, that overheard conversation. Naturally, their recitations will all be slightly different one from the other, either due to mishearing, or misremembering. Nonetheless, by carefully comparing each of the versions against each of the others, the court is able to reconstruct the basic content of that conversation, as well as a great majority of the finer details.

A very similar process is required when we attempt to reconstruct, as accurately as we can, God’s Word – the Scriptures. All those terms in the NIV footnotes (Masoretic Text, Septuagint, etc) are all witnesses, attempting to recite to us, as accurately as possible, God’s own Words. In this series of articles, we will introduce each of these witnesses, one by one, to better understand the unique contribution each makes, and how, taken together, they can give us great confidence in the accuracy of how the Scriptures have been passed down to us.

Bible Manuscripts through the Ages

Most of the Old Testament was written in Hebrew (with a little Aramaic, mainly in Ezra and Daniel). The New Testament, on the other hand, was written in Greek. When you read your Bible in a modern English translation, that translation will have been made directly from editions based on the Greek manuscripts of the New Testament, and the Hebrew manuscripts of the Old Testament, known as “Hebrew Bible” manuscripts.

The absolute earliest fragment of Hebrew Bible which we currently know about comes from sometime between the seventh and sixth centuries BC. In a graveyard in Jerusalem, at a place called Ketef Hinnom, two amulets were found, made from tiny rolls of silver. On one of those rolls was part of the prayer from Numbers 6 referred to as the Priestly Blessing.

The Ketef Hinnom amulets are, as far as we know, quite exceptionally early, but they only preserve a few sentences of the text of the Hebrew Bible. The earliest substantial collection of Hebrew Bible manuscripts currently available is the Dead Sea Scrolls. In addition to many other texts, the Dead Sea Scrolls contain thousands of fragments from over 200 biblical scrolls, written mainly in Hebrew. These date from roughly the mid-third century BC, through to the end of the first century AD. Many of these fragments are tiny, containing only a few letters, while others are far more complete—the most complete biblical scroll from Qumran, known as the Great Isaiah Scroll, is 734 cm long.

So, the Dead Sea Scrolls provide us with our earliest large-scale collection of Hebrew Bible manuscripts—an explosion of textual data, from the centuries immediately before and after the death and resurrection of Jesus. They are a resource of unimaginable significance, though not without their limitations. Most obviously: the great majority of the Scrolls really are just fragments. Of the 915 verses in the book of Proverbs, for example, the Scrolls preserve only fragments from 48 verses—many of which are represented by only a few surviving letters.

Sadly, after the Dead Sea Scrolls, the trail goes cold in our hunt for Hebrew Bible manuscripts (though many manuscripts containing translations of the Bible into Greek, Latin, Syriac, Ethiopic, and other languages, have survived). For the next seven or eight hundred years we have only a handful of Hebrew Bible manuscript remains. Scrolls of the Hebrew Bible must have continued to be produced and used, but very few traces of them survive. The few scroll fragments we do have from towards the end of this dark period have only survived because they were stored away for burial (according to Jewish practice then and now), but, by happy providence, never received that burial.

This dark period comes to an end around the year 900. Many fragments of Hebrew Bible manuscripts have survived from between AD 900 and AD 1000, as well as a handful of larger, more complete manuscripts. A great many Hebrew Bible manuscripts—some very complete and beautifully produced—survive from the eleventh century onwards. Many of these are currently housed in libraries in Cambridge, Oxford, London, Saint Petersburg, and other European cities. According to our current state of knowledge, the earliest complete Hebrew Bible manuscript (containing all the books of the Old Testament in one volume) still fully preserved today, dates from the year 1008. It is called the Leningrad Codex. We will come back to it later.

From our earliest evidence onwards, the text of the Hebrew Bible was copied onto scrolls (hence Dead Sea Scrolls). From antiquity, through the Middle Ages, and right up to the present day, Jewish ritual requires that the biblical text read in the synagogue must be read from a scroll, rather than any other format of book (remember Jesus reads from a scroll in Luke 4:16–20). Nonetheless, from about AD 900 onwards, a new—and immensely significant—type of Hebrew Bible manuscript appears on the scene, quite different to these scrolls: the Masoretic manuscript.

Masoretic Bible Manuscripts

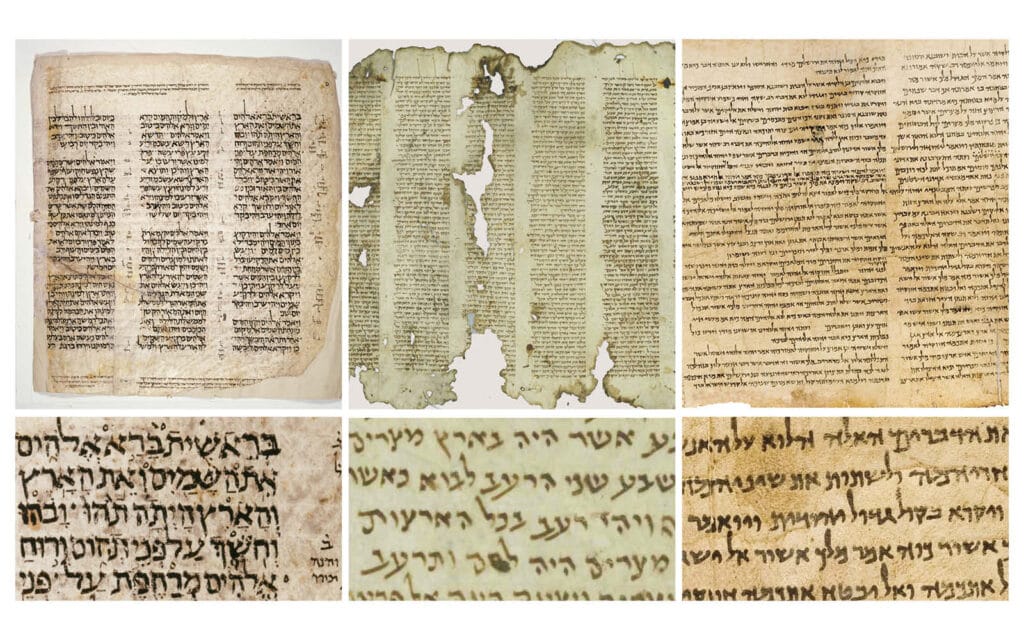

Let’s compare (just at the visual level for now) this new type of Hebrew Bible manuscript—the Masoretic manuscript—with the more traditional Hebrew Bible scroll.

On the left is a typical page from a masoretic manuscript (the Leningrad Codex, written in AD 1008). The middle images show part of a scroll of Genesis, from around AD 900, while the images on the right are part of the Great Isaiah Scroll, from about 100 BC. The Genesis scroll and the Isaiah scroll are thus separated in time by about 1000 years, but apart from the parchment color and script style they are quite similar—certainly when compared with the masoretic manuscript. The masoretic manuscript, unlike the scrolls, contains long notes in the top and bottom margins, and little notes squeezed between the columns of the biblical text. Looking more closely at the text itself: the masoretic text appears to have all sorts of dots, lines and circles above, below, and within the main letters, which are totally absent from the text in the two scrolls.

Another dramatic difference between the masoretic manuscripts and the scrolls, which is harder to see from the images above, is that the masoretic manuscripts are not scrolls; they are codices (i.e., they look and work like the books we are used to). What is the meaning of all this innovation in the masoretic manuscripts, after well over 1000 years of conservatism? What are the dots, lines and circles all about, and what are those marginal notes? To answer all these questions, we need to take a sidestep and consider the nature of the Hebrew language, and think more carefully about how the text of the Hebrew Bible was transmitted from well before the time of Jesus, to the “masoretic era.”

How does the Hebrew language work?

Ancient Hebrew, like many Semitic Languages, was a consonantal language. This just means that when it was written down, only the consonants of any given word were recorded; most of the vowels were unwritten (though, over time, four particular consonants began to be introduced to indicate some of the vowels). In addition, there was little to no punctuation in the earliest written forms of the language. So, for example, the phrase “the king’s word” would be written with the following consonants: דבר המלך. Or, in English transliteration: dbr hmlk.

This aspect of the written form of the language means that, frequently, a given word or phrase can be interpreted in multiple ways. So, for example, the phrase above could be read as intended: “the king’s word,” but it could also be read as: “the king spoke,” “speak, O king!,” “speak! Appoint a king!,” or even: “Plague was enthroned as king”!

Of course, context is almost always sufficient to clarify such ambiguities. Imagine if my wife gave me a heart-shaped card on Valentine’s Day, with the following text: “wll lv y fr vr”. The context would justify my reading this as “I will love you forever!” rather than the theoretically possible alternative: “I will leave you for Ivor!” Context is a wonderful thing: I feel loved and appreciated, and Ivor gets to keep his front teeth.

Nonetheless, even in context, some ambiguities remain—occasionally theologically significant ambiguities. For an example, we need look no further than the very opening words of the Hebrew Bible:

By applying one set of vowels and pauses to this consonantal, unpunctuated text, this sentence could be read as: In the beginning God created the heavens and the earth. And the earth was formless and void, and darkness was over the face of the deep. But by applying a different set of vowels and pauses, the same string of consonants could be read rather differently: When God began to create the heavens and the earth, the earth was formless and void, and there was darkness over the face of the deep.

Even in cases like this, however, the threat of ambiguity is more theoretical than actual. From the earliest stages of the transmission of the Hebrew Bible, the text was read out loud, not just stared at mutely (remember Nehemiah 8 and Acts 15:21: “For the law of Moses has been preached in every city from the earliest times and is read in the synagogues on every Sabbath”). Reading the text out loud obviously required the proper vowels, and the proper pauses, to be added in the correct places, thereby annulling the great majority of these potential ambiguities.

There is a great deal of evidence that from a very early stage, a traditional way of reading the plain consonantal text was developed: a Reading Tradition. The reading tradition clothed the consonantal text in all the vowels and pauses necessary for the correct understanding of the written consonants. This reading tradition was then passed on, orally, from generation to generation, just as the written, consonantal, text, was copied from generation to generation. In other words, when we conceptualize how the text of the Hebrew Bible was handed down from well before the time of Jesus, to the Middle Ages, we must envision two simultaneous strands to that transmission: one written (the consonantal text), and one oral (the correct reading of the consonantal text).

The Masoretes and the Masoretic Text

Now we are ready to return to those innovative Masoretic manuscripts. With the rise of Islam in the seventh century AD, and the concomitant increase in written documentation in the following centuries, there was a general cultural tendency in the Middle East towards increasing “textualization.” During this period, traditions that had previously been preserved orally, were increasingly written down. This move towards textualization was, naturally, felt by the Jewish communities living in the Middle East.

In seventh century Tiberias, in the north of the land of Israel, there arose a group of scholars whose particular expertise lay in the accurate preservation of both the written and the oral strands of the Hebrew biblical text. These scholars—The Masoretes (“transmitters of tradition”)—had themselves received the oral tradition regarding the accurate recitation of the consonantal biblical text. The great innovative genius of these scholars was that they found a way to write down (“textualize”) this recitation tradition which had previously been purely oral. They crafted two sets of symbols, each consisting of dots and lines. One set represented vowels, and the other represented the pauses and linkages required to divide the text into the correct sense-units (these latter signs are usually called “accents”). These vowels and accents were then written in and around the consonantal text itself. Thus, for the first time ever, the written and the oral strands of the Hebrew Bible were brought together in written form on the page.

Innovation and Preservation

To sum up: the Masoretic Text is the particular form of the Hebrew Bible found in Masoretic manuscripts from the ninth–tenth centuries onwards, and is the fruit of the genius of the Masoretes—the Jewish textual scholars active in Tiberias from the seventh to the ninth centuries AD. The Masoretic Text differs from previous forms of the Hebrew Bible; previously only the consonantal text was written down (in scrolls), while the ancient tradition of how those consonants should be read out loud was preserved orally. In the Masoretic Text, for the first time ever, the oral recitation tradition was made visible on the page, together with the consonantal text, thanks to the Masoretes’ creation of vowel and accent signs.

What we have done in this article is to explore, from a historical point of view, what the Masoretic Text is, where it came from, and what makes it different to the previous forms of the Hebrew Bible. We have thought of the Masoretic Text as a kind of medieval innovation. But we cannot claim to have begun to understand the Masoretic Text until we have thought about it from the opposite perspective: as an act of extraordinary—almost miraculous—preservation.

April 11, 2023

Notes

A version of this article was originally published on textandcanon.org as The Extraordinary Hebrew Text behind Your English Bible