Those were the words of Assyriologist George Smith after he translated a passage of this clay tablet in the British Museum in the early 1870s. Apparently, what he read was so extraordinary that, according to one writer, ‘he jumped up and rushed about the room in a great state of excitement, and, to the astonishment of those present, began to undress himself!’

The tablet itself was excavated a few years earlier at the site of Nineveh (modern day Mosul, in northern Iraq), found in the palace of the great Assyrian king Ashurbanipal (reigned 668–631 BC). As much a scholar as he was a conqueror, Ashurbanipal commissioned copies of literary and scientific works found in the libraries of Mesopotamia to be produced for his own personal collection. More than 30,000 tablets from this collection have been excavated, which are now in the British Museum. They represent some of the most expertly produced cuneiform writing that has survived, and the Flood Tablet is no exception.

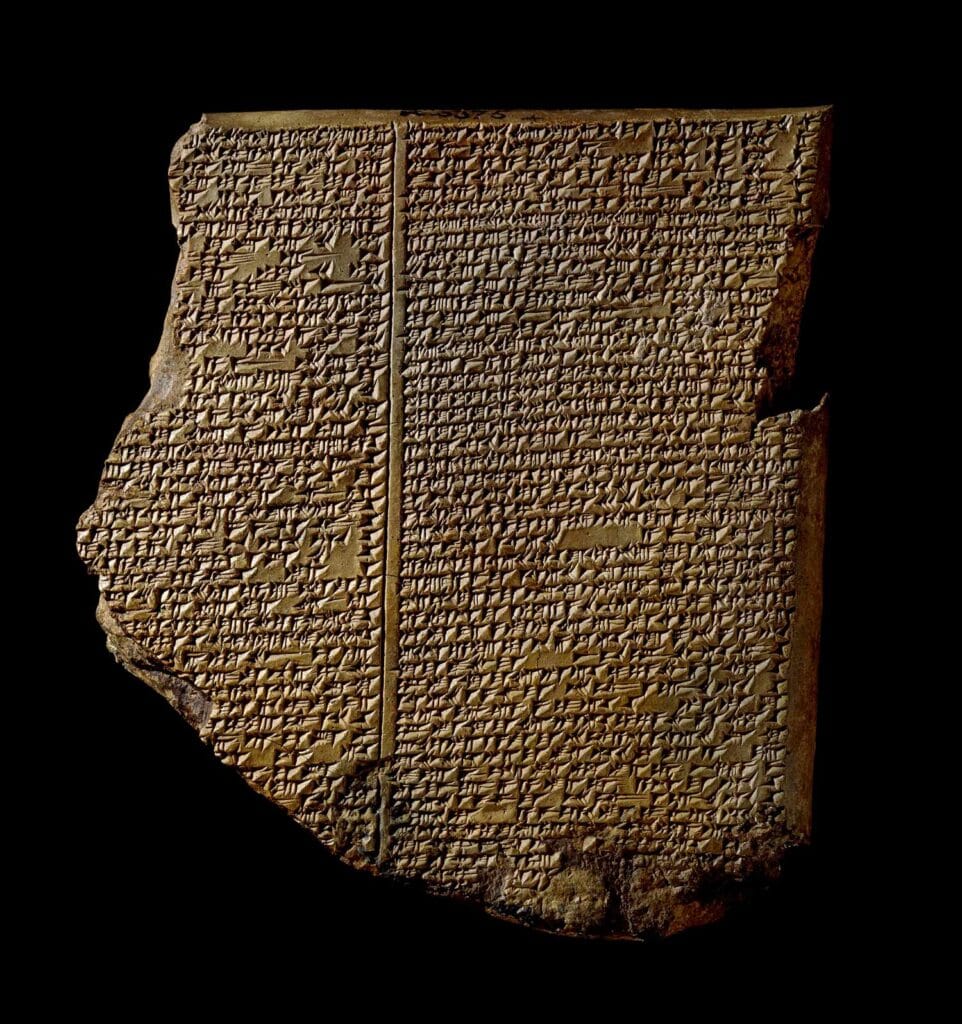

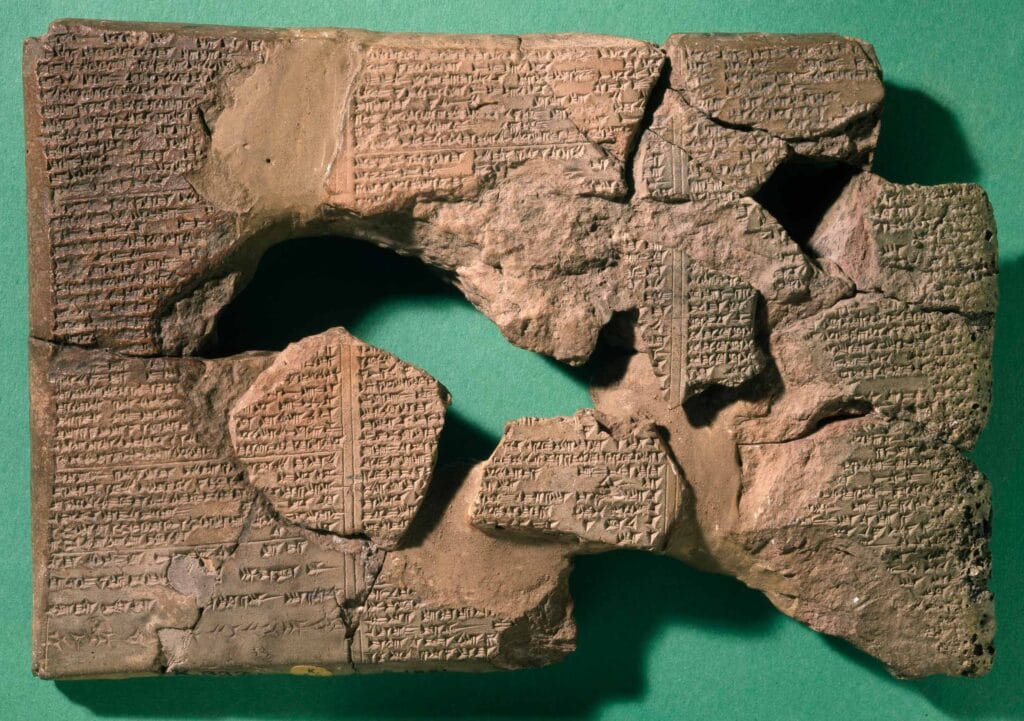

As you can see from the photo (fig. 1), it is, unfortunately, broken. One and a half columns of text survive on the front, with another column and a half on the back. Originally, it would have been made up of three columns on each side (like the partially restored tablet in fig. 2), with the whole thing being roughly the same size as a modern touchscreen tablet. In ancient Mesopotamia, the chapters of stories were recorded on separate clay tablets, and both tablets pictured contain copies of the eleventh and penultimate chapter of the famous Gilgamesh Epic.

The Epic of Gilgamesh is a beautiful, timeless story of pride, love, loss, and the search for life’s meaning. Grieving the death of his companion Enkidu and fearing his own end, Gilgamesh sets out in the Epic’s second Act to find the one man known to have gained eternal life—a man named Uta-napishti. After a long and arduous quest, Gilgamesh finally meets Uta-napishti, who tells him the story of how he came to live forever. It is this story-within-a-story that takes up most of the Gilgamesh Epic’s eleventh chapter. Its rediscovery by George Smith, on the basis of tablets such as these, caused quite a stir in Victorian Britain and around the world. Indeed, it continues to do so today.

‘A brother could not see his brother, people could not be recognised through the rain, the gods feared the flood . . . The wind blew for six days and nights. The flood, the storm, it flattened the land’ (Gilgamesh XI.112–113, 128–129). This story told by Uta-napishti, when recounted by Smith at an event attended by the Prime Minister and Archbishop of Canterbury, sounded remarkably familiar. Long ago, the gods decided to destroy the world with a flood. One of these gods told Uta-napishti to build a boat to save his life, and to bring his family aboard, along with every type of animal. The flood comes and only those on board the boat survive. Eventually, the boat runs aground on a mountain, and Uta-napishti sends out birds to see if they can find dry land. Uta-napishti then makes sacrifices to the gods, who come to his boat and grant him eternal life.

The similarities between Uta-napishti’s story and the story of Noah’s ark in Genesis are obvious. But what do these similarities tell us? What is the relationship between these two stories?

One possible answer, and perhaps the most popular today, is that the writer of Genesis had read the Gilgamesh Epic, and rewrote the story in line with his own theology, removing references to a pantheon of gods in favour of the one God. Whether or not the writer of Genesis was familiar with Gilgamesh, such an explanation is too simplistic.

The version of the flood story found in the Gilgamesh Epic is just one of several known from the ancient Near East. Around 90 years after George Smith’s discovery, the late Alan Millard (1937–2024) made a discovery of his own, finding two large tablets that had been sitting in a drawer in the British Museum for decades. These tablets are around a thousand years older than Smith’s, and tell a very similar story, but with a hero called Atra-hasis. A Sumerian composition of a similar date also contains a story of a flood, survived by one man in a boat filled with animals. An even older Babylonian tablet provides a different version of the story. At least one other version was known in the Syrian city of Ugarit in the late second millennium BC. It would seem that the ancient Near East (to say nothing of other parts of the world where flood stories are known) was awash with stories of a man who, thanks to the warning of a god, survived a divinely ordained flood, preserving animal life with him on his boat.

These are just the versions of the story that were written down and happened, not only to survive in the ground for thousands of years, but to be found by archaeologists. Though we can’t know, we could imagine that every family in the region told such a story. While the surviving written versions share various parts of the Genesis version’s general outline, they all differ significantly from it (and, to varying degrees, from each other) in language, style, and detail. Comparing their differences and similarities is a fascinating endeavour, but it would be unwise to assume that the account we have in Genesis is directly based on, or inspired by, any of the other specific written versions of the story that we know about.

The existence of other versions of a story so well known to us from Genesis can be somewhat disconcerting. But if the event as described in the Bible did in fact take place, then the prevalence of such versions would by no means be surprising.

October 9, 2024