I have stored up your word in my heart: manuscripts and memorisation

Article

2nd September 2022

Dr Kim Phillips explores the lost art of memorisation and considers what medieval memory techniques can teach us today.

Picture, in your mind’s eye, a shepherd walking up to the crest of a green hill. Walk alongside him. As you reach the top of the hill you lie down on the soft grass. You see a river below you, sparkling in the sunshine as it winds gently along. When you reach the river, you spot a footpath running alongside, and turn to follow it. The footpath turns away and starts to lead steeply downhill into a darkly wooded valley. A cloud covers the sun, and a shadowy gloom draws in. It’s cold. But the shepherd is still beside you; you hear the gentle swish and tap of his staff. He leads you into a small clearing where a table is laden with food. You sit. From the shadows at the edge of the clearing hate-filled eyes stare at you. But at the table, with the shepherd, you know you are safe. He takes a flask of scented oil and pours some over your head. He picks up a flagon of wine and fills a cup in front of you—so full that it overflows onto the table. Lifting your eyes from the cup and the table, you see that you are no longer in the dark valley, but in the shepherd’s own house.

We have just imagined our way through Psalm 23, of course. In the process, we have employed some simple memory techniques used for thousands of years to aid the process of word-for-word memorisation of long stretches of text.

Medieval memory books

The verbatim memorisation of large stretches of the biblical text is almost entirely neglected today. We might do ‘memory verses’, but what about ‘memory chapters’ or ‘memory books’? For medieval Jews and Christians, on the other hand, large-scale scripture memorisation was a vital part of spiritual formation. Could it be that this neglect, perhaps encouraged by the ready access we have to the bible via our phones, means we are missing out on a once-treasured tool for discipleship?

Large-scale text memorisation played a significant part in education and spiritual formation throughout antiquity and the Middle Ages. This involved the disciplined training of one’s memory via intricate mnemonic techniques. Memorisation devices and techniques were discussed at length by various classical and medieval authors. This training aimed not at the ability merely to reel off large stretches of text parrot-fashion, but rather to encode a text in one’s memory in such a way that any part of the text could be retrieved at any point, or systematically searched. Random access, rather than sequential access, in computing terminology. Using these mnemonic tools, some scholars were able to memorise (either verbatim or at least at the level of the succession of ideas) huge numbers of texts. In what follows, however, I would like to consider a more modest target for memorisation: the 150 Psalms of the Psalter.

In historian Mary Carruthers’ fascinating study of memory in medieval culture, she notes: ‘The book which Christians, both clergy and educated laity, were sure to know by heart was the Psalms.’ In a recent study of manuscripts created as memory aids

by members of the medieval Jewish community in Egypt, I have come to similar conclusions. Among all the biblical texts, the Psalter is the most frequently memorised, and this was not merely the feat of an exceptional minority, but was attained by a range of the Jewish community. Let’s spend some time with one such manuscript, to get an idea of how it works.

The shorthand Psalter

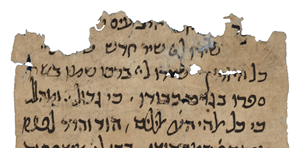

Here is a two-page spread from a manuscript from the Ben Ezra Synagogue in the city of Fustat (Old Cairo), Egypt. It is written on paper, rather than parchment, in this oddly long, thin format. Other manuscripts of this shape also tend towards being user-produced documents, often for personal or liturgical use. In the books we are used to today, the hinge of the book is vertical, and we turn the pages horizontally, from right to left. In this manuscript, the hinge is horizontal; you can see it halfway down the leaf, marked by six small dots where the separate leaves would have been stitched and folded together to make a set of pages known as a quire. One turns the pages of this manuscript from the bottom upwards. During the 900+ years this manuscript lay hidden in the Genizah, some of it was lost, or destroyed. Nonetheless, in its present state it contains almost all of Psalms 42–106: Books 2, 3 and 4 of the Psalter.

Let’s take a closer look, to see how the manuscript works as an aide-mémoire. Pictured on the left is Psalm 42 (“As the deer longs for streams of water…”). This manuscript is written in ancient Hebrew, which is read from right to left across the page. And below the manuscript image is the text written out in English. The highlighted words reflect what is written in the manuscript. The rest had to be recalled from memory.

To the choirmaster. A maskil of the Sons of Korah.

As the deer pants for flowing streams, so pants my soul for you, O God.

My soul thirsts for God, for the living God. When shall I come and appear before God?

My tears have been my food day and night, while they say to me all the day long, “Where is your God?”

These things I remember as I pour out my soul: how I would go with the throng and lead them in procession to the house of God with glad shouts and songs of praise, a multitude keeping festival.

Why are you cast down, O my soul, and why are you in turmoil within me? Hope in God; for I shall again praise him, my salvation and my God.

My soul is cast down within me; therefore I remember you from the land of Jordan and of Hermon, from Mount Mizar.

Deep calls to deep at the roar of your waterfalls; all your breakers and your waves have gone over me.

By day the Lord commands his steadfast love, and at night his song is with me, a prayer to the God of my life.

I say to God, my rock: ‘Why have you forgotten me? Why do I go mourning, because of the oppression of the enemy?‘

As with a deadly wound in my bones, my adversaries taunt me, while they say to me all the day long,“Where is your God?”

Why are you cast down, O my soul, and why are you in turmoil within me? Hope in God; for I shall again praise him, my salvation and my God.

As you can see, the manuscript usually records the first couple of words of each verse and assumes that those would be sufficient to prompt the recall of the rest. As impressive as these tiny prompts for recall already are, they’re only the tip of the iceberg. At other points in the manuscript the biblical text is abbreviated far more strictly.

For example, Psalm 104 (image top right). Of the 240 Hebrew words in this Psalm, only 14 are represented in the manuscript (taken from the beginning and the end of the Psalm). What’s more, of those 14 words, five are themselves written in some sort of abbreviated form. The manuscript’s author knew this Psalm so well that after the initial few words to start him off he needed no more prompts to recite the entire text.

In fact, in another portion of the manuscript there is an intriguing hint that this scribe was even more deeply familiar with the Psalms than implied thus far. The section which contains Psalms 73–89 (Book Three of the Psalter) is written in a numbered list (image bottom right). What was the purpose of this list? It’s unlikely, for two reasons, that the list was simply intended to record the correct order of the Psalms. Firstly, that order could easily be found by flicking through the manuscript itself. Secondly, the amount of each Psalm that is recorded is far more than would be required if the only purpose of the list was to disambiguate one Psalm from another. Instead, the clue to the purpose of the list seems to be bound up with the amount of each Psalm recorded.

Some Psalms are only afforded a single line of text, while others are allowed two lines. The writer of the list has been careful always to include not only the Psalm’s heading, but also the beginning of the main content of the Psalm. When the heading is short (such as “A Psalm of Asaph” at the beginning of Psalm 73), there is enough space on the one line to include the first chunk of content: “Surely God is good to Israel.” On the other hand, when the heading is long (such as “For the choirmaster; do not destroy; a Psalm of Asaph—a song” at the beginning of Psalm 75) the writer of the list has taken a second line in order to include the first few words of the Psalm’s main content: “We give thanks to you, O God.”

We can surmise that these few words of the main content—alone—would have been enough to guide the reciter through the recitation of Book Three of the Psalter from memory. In other words, the memory cues we saw above for Psalm 42, where the first few words of each verse were given, were just for beginners! Eventually, the aim was to be able to recite all the Psalms completely by heart, just using the list of first lines to help keep the Psalms in their correct order.

Memory training

How on earth was the owner of this manuscript able to achieve such an impressive feat of memorisation? The manuscript itself can give us some hints, but we can also turn to some of the memory training manuals—-some as old as the Graeco-Roman period—for extra information. Let’s revisit our journey through Psalm 23 as a worked example.

First, notice how visual the whole process was. We did not start with words, but with mental images, which are much more ‘sticky’ when it comes to memorisation. We could boil down the entire journey to a bare list of the key images: green hill; river; path; dark valley; shepherd companion; shepherd’s staff; feast table; cup; shepherd’s house. If we wanted to, we could ‘chunk’ these images still further, into three groups of three: three sunny images (green hill; river; path); three valley-based images (dark valley; shepherd companion; shepherd’s staff); three feast-based images (table; cup; house). Thus, we have boiled the Psalm down into three visually and mnemonically rich images: sunshine; valley; feast. This sort of multi-level chunking is particularly useful with long Psalms, as it helps avoid overly long sequences of images. For example, when memorising Psalm 104, I broke down the 35 verses into seven chunks. Each chunk was then broken down into smaller units.

–

The Cairo Genizah

Our manuscript comes from the Ben Ezra Synagogue in the city of Fustat (Old Cairo), Egypt. A large Jewish community flourished in Fustat between the tenth and thirteenth centuries and became one of the key centres of medieval Jewish life. We know a vast amount about the life of this community thanks to the preservation of a store of over 200,000 of their documents. The store (known as a ‘Genizah’) housed worn-out manuscripts and documents which had come to the end of their useful life and were awaiting the formal burial required for them under Jewish law. Thanks in part to the so-called ‘mad Caliph’ Al-Hakim, and his attack on the Ben Ezra Synagogue in 1012, these documents never received that burial. But that’s another story. This treasure trove of texts lay undisturbed for centuries, until they were uncovered in the 1890s and brought to Cambridge University Library, where the Genizah Research Unit was established to conserve and study the manuscripts.

These documents give us technicolour access to strands of medieval history that are usually beyond our reach. By a series of historical ‘accidents’, the Genizah ended up storing an eclectic mix of the ephemera of life: pre-nuptial agreements, marriage documents, divorce documents, book lists, business documents, begging letters, court discussions, love poems, recipes for medicines, shopping lists, amulets against scorpion stings, along with 25,000 Bible fragments and thousands of other key Jewish texts.

–

Second, notice how I tried to make the images not simply visual, but as striking and multi-sensory as possible. So, it wasn’t just a river, it was a river whose water was sparkling in the sunshine. We felt the chill as we entered the gloomy, wooded valley. We smelled the anointing oil. We could have added much more sensory detail: the feel of the springy turf as we lay at the top of the hill on the green grass; the sound of the river chuckling and gurgling along; the look-over-your-shoulder feeling of apprehension as we walked into the dark valley. Modern research has confirmed what was already understood and remarked upon by the ancients: the more striking and multi-sensory the image, the better it sticks in the memory.

Lastly, notice that our memory-cue images did not stand alone—they were linked one to another. In this particular case, they were linked by an imaginary journey, but other links are possible. The key is that image number one must help bring to mind image number two, and so on. What did we see from the top of the green hill (image one)? Of course—the river (image two). At the river we spotted the path; the path led to the dark valley; in the gloom we felt the presence of our shepherd companion; we heard the swish of his staff; the path led to the table; on the table was the cup; lifting our gaze from the cup, we found ourselves in the shepherd’s house.

So, we have broken the Psalm down into a sequence of linked, multi-sensory images. This sequence then forms a kind of framework, into which we can slot the precise words of each line of the Psalm. Of course, we still have to work hard to grasp the exact wording of each line, but the process is made much more straightforward once we have the framework in place.

Finally, we must tackle another objection. Someone might say: it’s all very encouraging hearing about memorisation in a pre-print era, but what is the merit of memorising a text in our day and age, when we can carry around entire libraries on our smartphones? We probably assume that twelfth-century people like the scribe behind the manuscript above developed these habits of memorisation because written texts were hard to get hold of. However, medieval Christian scholars, such as Hugh of St Victor, who discuss memorisation appear to have viewed the matter differently. First and foremost, memorisation was understood to be a crucial part of spiritual formation. The intensive concentration and focus on the text required to commit it to memory, and the subsequent meditation on the text made possible once the text is written on the tablet of our hearts, shapes us in a very particular way. It is as though the words work their way into the warp and weft of our very being. Isn’t this exactly the point made in the Scriptures themselves?

I have stored up your word in my heart,

that I might not sin against you. (Psalm 119:11)