Can you imagine reading your Bible without chapter divisions?

The original authors of Scripture probably used some punctuation and paragraph divisions, but they almost certainly did not use chapter divisions and numbers. Yet chapters permeate editions of the Bible today and they influence how we read Scripture, often unconsciously.

Think about how modern chapter numbering tends to determine sermon texts, yearly Bible reading plans, and classroom assignments. For example, in my seminary Bible survey classes, I had to write a one-sentence summary of every chapter in the Bible. But what if the chapter numbers don’t indicate a shift or division in the biblical text itself, or what if the chapter breaks are in bad places?

The story of how our modern chapter system arose is an interesting one, and it has implications for our Bible reading today.

Why were standardised chapters needed?

Modern chapter divisions arose in the early thirteenth century AD in the midst of an intellectual climate that needed navigational aids for studying the Bible. New study tools like concordances listed all the uses of a given word in the entire Bible. Chapter references helped users find the exact place in their Bible, so that they could read the fuller context. We take for granted that we can easily find Romans 12:6, but such was not the case prior to the thirteenth century.

With the rise of universities, the study of the Bible moved from monasteries and churches into classrooms. Students and teachers literally needed to be on the same page to discuss Scripture. But most Bibles of the time did not use page numbers and there was not yet a standardised chapter/verse system.

The Latin Bibles used in Europe had a multitude of chapter systems. These chapter systems were inherited from the Old Latin tradition and various revisions to Jerome’s Latin Vulgate. New Testament scholar Hugh Houghton has identified 16 different chapter systems in Old Latin manuscripts of John’s Gospel, containing between 13 to 68 chapters. This lack of standardisation was a problem if people wanted to easily navigate to the same passage of Scripture.

How did the modern chapter system arise?

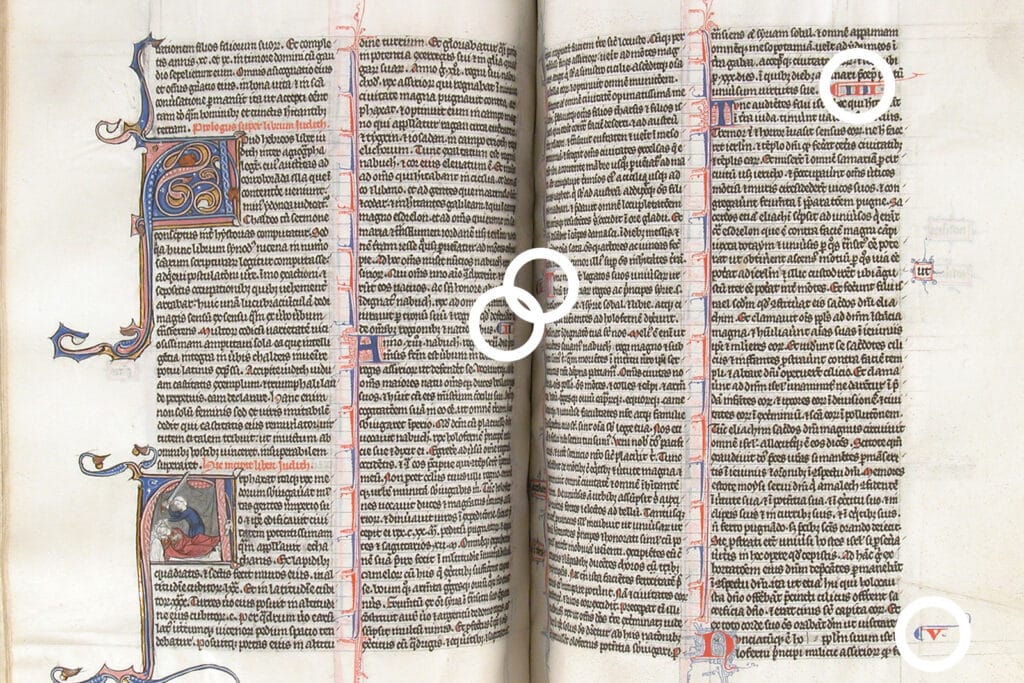

The modern chapter system is closely linked to so-called ‘Paris Bibles’ of the thirteenth century. These Latin Bibles were originally produced in Paris, but eventually found their way to other parts of Europe. Paris Bibles popularised a new kind of Bible, a portable, single-volume, standardised format that still characterises Bibles used today.

Nowadays, people take for granted that everyone can have their own personal copy of the Bible, which they can easily take to church or school. But such was rare throughout most of church history because a copy of the entire Bible would span multiple volumes or be one very large book. A portable, one-volume Bible was made possible through technological advancements with thinner parchment and new scribal practices of writing in smaller script and with more abbreviations. The Paris Bible’s new portable format was especially popular with Dominican and Franciscan friars who were travelling preachers and needed a Bible they could easily carry.

We can also easily take for granted that Ruth comes after Judges, or that 1 and 2 Chronicles comes after 1 and 2 Kings. But different manuscripts had variations among themselves regarding the order in which the books of the Bible appeared. And when a Bible spans several volumes, one can reshelve the individual volumes in different orders. Once the Paris Bibles popularised having the entire Bible in one volume, the order of books mattered more. There were already some common ordering principles, but the Paris Bibles helped to standardise an order similar to what we find in modern Bibles today.

Standardised chapter divisions and numbers

Paris Bibles also standardised the chapter divisions and numbers that would become the modern chapter system. Many scholars think that scholar and clergyman Stephen Langton (c. AD 1150–1228) was responsible for creating these chapter divisions.

The idea that Langton created the modern chapter system comes from two sources: First, some of Langton’s biblical commentaries contain chapter divisions nearly identical to modern ones. Secondly, notes in the margins of two medieval manuscripts ascribe the division and numbering of chapters to Langton.

Why did Langton create chapter divisions?

Langton studied at the University of Paris and lectured in theology from about AD 1180 to 1206, becoming the Archbishop of Canterbury in 1207, after which he focused more on ecclesiastical politics. During Langton’s time teaching in Paris, the many different chapter systems in Latin Bibles would have caused confusion in classroom settings if teachers and students all had different versions.

Beyond just the practical implications, Langton also had deeper criticisms of existing chapter systems. He saw them as inconsistent in length and not helpful to readers’ understanding. He seems to have had two goals: to create chapters of equal length and to have unity of subject matter within them. But these two goals are not always compatible with each other. If we examine the modern chapters we have inherited, we realise that Langton often struggled to reconcile these two goals, yet the fact that this system is now universal shows that he was remarkably successful.

Sources for Langton’s chapter divisions

Langton did not ‘create’ the modern chapter divisions all by himself (as some imply when talking about modern chapter divisions). He was indebted to the chapter divisions in the Latin Bible of Alcuin of York (produced AD 796–804), and the Latin Bible of Theodulf, bishop of Orléans (produced circa AD 800). Three other individuals were also developing chapter divisions prior to Langton in the twelfth century: Peter Comestor, Peter the Chanter, and Simon the Abbot of St Albans monastery. All of these pre-existing chapter systems likely influenced Langton and the editors and scribes of Paris Bibles.

We can conjecture that Langton engaged in a combination of tasks: he was taking from earlier Bibles, improving their divisions, creating his own, and promoting the use of the new chapter system—all in an effort to aid his university Bible teaching.

In other words, Langton’s chapter system was not a one-time solo effort, but a gradual development over 25 years of teaching, indebted to earlier Latin chapter systems and to other scholars doing similar work. His chapter divisions do not match up perfectly with our current system, which implies that others continued to improve his chapter system. Those who finished Langton’s work were probably Philip the Chancellor of Notre Dame, Hugh of St Cher, and the publishers of the Paris Bibles.

Implications for Bible reading today

Modern chapter divisions were created to help us as readers. Along with verse numbers, section headings and footnotes, they help us navigate and interpret the biblical text. While sometimes these reading aids might not accurately reflect the text’s meaning, we can still be thankful that we have them.

But remember: all chapter systems (ancient and modern) should be regarded as the fallible interpretation of scholars; they are not authoritative and do not originate from the biblical authors. Thus, readers should feel free to ignore and/or disagree with modern chapter divisions.

With this in mind, it is useful to study other ancient chapter systems to gain fresh perspective on the structure of biblical texts. Tyndale House’s New Testament Project studies the chapter system found in the Byzantine family of New Testament manuscripts, a system that arose in the fifth century AD. By looking at other chapter systems, we can eliminate overfamiliarity with modern chapters and gain new insights into the structure and flow of biblical texts.

November 22, 2023

Notes

Header image: Stained glass window showing Stephen Langton (St Dunstan-in-the-West. Flickr: Michael Day, CC BY-NC 2.0), with image behind of inside spread of a Paris Bible (Bible, French ca. 1250-70. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1997.320. Public Domain).