If you read an English Bible, you may notice footnotes telling you that some manuscripts read something different from what is printed in the main text. The biblical texts have come down to us through a process of copying Hebrew or Greek manuscripts. Scribes made quite a few mistakes, so we sometimes find places where the manuscripts do not all agree. In those instances, the translators might look to see what the ‘best’ manuscripts or the majority of manuscripts say and try to evaluate what the author originally wrote, and so we get many of our footnotes.

However, you may encounter other footnotes informing you that the ‘Old Latin’ or the ‘Latin Vulgate’ versions say something different. This might raise the question, why should you care? You may have heard it reported, for example, that we have over 5,000 manuscripts of the New Testament in the original Greek. If that’s the case, why on earth do we need the Latin translations? If we have all this evidence in the original language, why do translators bother with readings from an ancient version?

Why translators read translations

To begin answering those questions, we might start by addressing why translators bother with any ancient translations at all. Usually, modern English Bible translators are offering a translation of the words found in the dominant critical edition of the original language text: typically the most recent edition of the Biblia Hebraica for the Hebrew Old Testament and the United Bible Society/Nestle-Aland text for the Greek New Testament. But there are two problems that ancient versions can help translators resolve.

The first is when disagreements or oddities among the original language manuscripts make it uncertain what the original reading was. The translators can consult ancient versions to settle the dispute. If most or all of the versions favour one reading over the other, the translators might side with that reading. For example, in Judges 18:30 (ESV), we read the following:

And the people of Dan set up the carved image for themselves, and Jonathan the son of Gershom, son of [Manasseh/Moses], and his sons were priests to the tribe of the Danites until the day of the captivity of the land.

The problem for translators is that many Hebrew manuscripts say that the Jonathan in question is the grandson of Manasseh, but many others say instead that he is a descendant of Moses. If all the translators had to go on were the Hebrew manuscripts, they may have been torn between the two options. However, as the 2011 NIV footnote states, both the Greek Septuagint and the Latin Vulgate support the reading ‘Moses’ here. The NIV translators therefore chose ‘Moses’ as the better option, as did the editors of the ESV and other translations.

The second problem is when the original language manuscripts agree on what the text is, but the meaning of an unusual word or phrase is unclear. In this case, the versions function as a translation aid, helping to clarify the meaning. For example, in Job 6:14:

He who [למָּס] kindness from a friend forsakes the fear of the Almighty.

If you are wondering, ‘What on earth does למָּס mean?’ you’re not alone! This word, at least in this form, occurs nowhere else in the Hebrew Old Testament. This, among other factors, led the ESV translators to simply concede in a footnote that ‘the meaning of the Hebrew word is uncertain.’

Thankfully, the Latin Vulgate (and a few other sources) translates this passage quite clearly, using the common word tollit (‘take away’ or ‘withhold’). So the ESV translates this verse as, ‘He who withholds kindness from a friend forsakes the fear of the Almighty.’

Which translations translators read

From the examples above, you might deduce that, for the purposes of modern translators, the value of any ancient version rests on at least two key things. First, to help us figure out the oldest readings in the original language, the version must have been translated from that language. It also ought to be sufficiently old. A translation made in the third century of the Christian era can inform us what words the translators were seeing in Greek or Hebrew manuscripts made up to that time. This would be very useful information if we want to recover the first-century text of the New Testament. But a translation made in, say, the eleventh century would generally be less useful since it can only be expected to tell us what sorts of readings were available a thousand years after the New Testament was written.

Secondly, the version needs to be sufficiently clear and reliable, and its manuscripts need to agree with each other enough to discern the original reading of the translation. Even if a translation is old, it is of little use if we cannot reliably determine what it initially said, or what Greek or Hebrew reading the translator was looking at. If a translator was inconsistent in his method, or if a translation was produced by many people with varying degrees of competence, it may be less useful than a somewhat younger translation produced by a competent and consistent translator.

This helps explain why the Old Latin and Vulgate are both cited in modern translations. Both are ancient sources derived from the original languages, which can therefore shed light on the underlying Hebrew and Greek texts. But to better understand why multiple Latin versions are used today, it will be useful to briefly examine the history of these translations.

The Vulgate solution to an Old Latin problem

Latin manuscripts that seem to represent a translation made prior to Jerome’s in the late fourth century are typically classed as Old Latin. ‘Old’ is more of a relative term in this context. The occasion for this translation seems to stem from the cultural shift in the Roman empire when Latin displaced Greek as the dominant language. In the New Testament period and the century immediately following, Greek was the lingua franca of the Roman empire. This is why all of the New Testament documents were originally written in Greek, as well as most of the writings of the second century Church (for example, the epistles of Clement, the Didache, and the Shepherd of Hermas).

This seems to change from around the turn of the third century. From then on, more and more of the writings of Church Fathers were in Latin, as were many of their quotations of the Old and New Testaments. At least within the western Church, Latin became the dominant language in this period and Greek was gradually forgotten. As fewer and fewer western Christians were able to understand Greek, a Latin translation became increasingly necessary. The Old Latin version met this need.

Strictly speaking, the Old Latin may not be one version but several, made in the late second to early third centuries. Some scholars suggest that the Old Latin tradition might possibly descend from a single translation of the entire Bible. Most, however, have maintained that each book of the Bible (or small collection of books) was translated individually, likely by multiple people in multiple places, though it is possible that a single translation of each book was made initially, and these translations underwent many revisions in the third and fourth centuries. Whatever the case may be, the end result is the same: by the end of the third century, all of the Old and New Testament writings had been translated into Latin. Today, these translations are collectively referred to as the ‘Old Latin’.

However, by the second half of the fourth century, the Old Latin manuscripts disagreed with each other to such an extent that scholars such as Augustine and Jerome complained of struggling in vain to find two that agreed. This was the problem that the Vulgate was meant to solve.

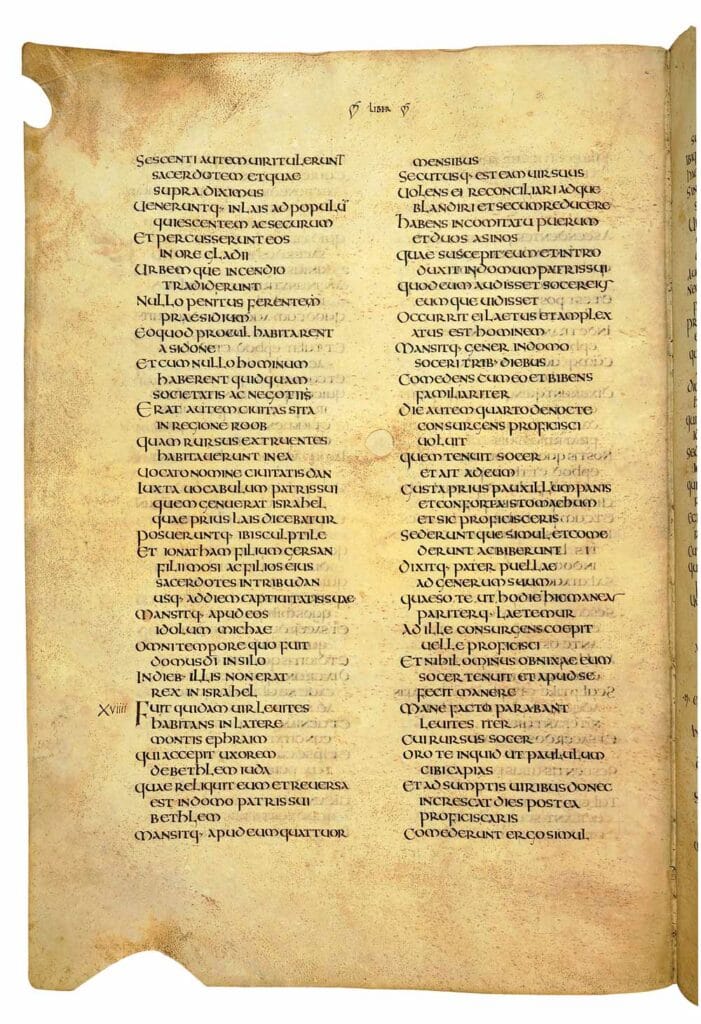

In the latter half of the fourth century, Pope Damasus commissioned Jerome to produce a revision of the Old Latin for the four Gospels. Jerome seems to have done this by comparing the various Latin readings and correcting them as necessary to correspond to the Greek text available to him. He completed this work on the Gospels prior to Damasus’s death in AD 384, after which Jerome turned his attention to the Old Testament, producing a fresh translation of the Hebrew Bible into Latin. The remainder of the New Testament seems to have been translated in the early fifth century, though by a mysterious somebody (or somebodies) other than Jerome. This later translation work came to be regarded as part of the same project begun by Jerome. Eventually, this combined work became known as the ‘Latin Vulgate’.

Though somewhat less ancient, the Vulgate has a few advantages over the Old Latin. Since the majority of the Vulgate was produced by a single competent translator and revisor, the translation method is somewhat more consistent. Jerome produced a generally tight, literal translation of the original languages that was nevertheless smooth and readable in Latin. Moreover, while Jerome made his Old Testament translation directly from Hebrew manuscripts, the Old Latin seems to have been translated from the Greek translation of the Hebrew. This means that, of the two, only the Vulgate presents a direct witness to the ancient Hebrew text. Finally, whereas the Old Latin witnesses are generally perceived as being more diverse or even chaotic in their quality and the types of readings they present, Vulgate manuscripts show comparatively more agreement, in addition to being much more numerous.

Why Translators Love Latin

Both the Vulgate and Old Latin prove useful tools for modern translators. Potentially reaching as far back as the second century, Old Latin manuscripts may at times present a form of the text as ancient as any original language manuscript, at least for the New Testament. But the greater clarity and consistency found among Vulgate manuscripts seems to engender more trust among modern translators and editors. Being produced primarily in the fourth century, the Vulgate can still be numbered among the most ancient witnesses to the entire Old and New Testaments. The general quality and consistency of the version, along with its relationship to the original Hebrew of the Old Testament, make it particularly valuable for resolving the two problems mentioned early in this article. It helps modern translators recover the most ancient form of the Hebrew or Greek text, and it clarifies the meaning of otherwise obscure terms in the original languages.

October 9, 2024